Summary: LSD microdoses (13 μg and 26 μg) changed psychological and behavioral functioning, but the effects were relatively modest and many areas of functioning were not altered at all. Microdosing did not have a positive effect on cognitive performance.

Authors: Anya K. Bershad, Scott T. Schepers, Michael P. Bremmer, Royce Lee, Harriet de Wit

DOI: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2019.05.019

Link: https://www.biologicalpsychiatryjournal.com/article/S0006-3223(19)31409-X/fulltext

Published: 2019

Intro

Psychedelics like LSD and psilocin are mostly known for their hallucinogenic, insightful, and therapeutic effects. They significantly alter perception, emotion, creativity, and more, while also impairing some aspects of normal functioning. A different way of using these drugs, known as microdosing, began attracting users in the 2010s and there are now countless people who attribute positive effects on mood, anxiety, and cognition to the practice.

Microdosing involves using sub-hallucinogenic doses, typically one-tenth to one-twentieth of a standard dose. For LSD that comes out to ~10 to 25 μg. Whereas high doses are taken infrequently because of tolerance and the sheer intensity of the experience, microdoses are less impairing, exhausting, and powerful, so people can take small amounts every 3 to 5 days. The anecdotal reports are not always positive, but enough people have reported benefits to generate a lot of interest.

The hype and excitement around microdosing has grown much faster than formal research on the topic. Psychedelics have been studied for decades, but the research has centered around large doses, so we know very little about microdosing. The lack of blinded, placebo-controlled research has caused some people to question whether microdosing is really as efficacious as its proponents claim. Because it is intended to be a “background” kind of drug use or, at most, an alternative to drugs like caffeine and nicotine, it’s possible at least a portion of the subjective effects stem from the placebo effect. The placebo response could be especially problematic with this kind of drug use because people are taking a substance that is known to have very powerful effects, which thereby affects their expectations and experience.

A couple of microdosing papers have been published in recent years, but they have either relied on subjective reports online and in observational settings or they have looked at effects on areas of functioning not directly relevant to users. But a study published earlier this year by researchers at the University of Chicago has given us a look at the psychological, cognitive, and physiological effects of microdosing in a controlled setting.

Background

Only a handful of studies about microdosing have been published, typically using self-reports from users to determine the effects. A review of the literature in 2019 found four scientific papers in which users reported benefits like improved mood, energy, and cognition, along with greater open-mindedness and a drop in negative attitudes (Polito, 2019). An uncontrolled study of 909 people recruited via social media and subreddits found microdosing was correlated with greater open-mindedness, reduced negative emotionality, reduced incidence of dysfunctional attitude, and increased creativity (Anderson, 2018). Among the microdosers, 65% used LSD and 28% used psilocybin.

One of the only controlled studies demonstrated changes in time perception, though that is fairly irrelevant knowledge for people interested in microdosing (Yanakieva, 2018).

More research has been conducted in animals, where small doses of drugs like DMT and psilocin appear to have the potential to improve mood and anxiety (Cameron, 2019), but it is not clear whether the more substantial benefits of high-dose experiences can be replicated with small, frequent doses. And there are some conflicting results, such as research showing animals are more anxious on a low dose of DMT (Horsley, 2018).

One of the exciting possibilities is that sub-hallucinogenic doses will improve learning and flexibility in one’s thinking, helping to overcome rigid thought patterns, but investigating that aspect of the practice is difficult. As of 2019, thousands of anecdotes support microdosing being relatively low-risk and potentially useful, but we know very little about what multiple administrations per week will do, given that is not how psychedelics have historically been used. Caution is warranted!

While microdosing is intended to be something you can include in your daily life, it should not be combined with driving and other activities that require a high level of functioning to keep yourself and others safe. Because we do not know how strong its potential impairment is and some people do report cognitive and perceptual disturbances either due to accidentally using too much or because of a personal sensitivity to impairing effects, it cannot be considered safe to drive.

Methods

20 healthy adults participated in four sessions, during which they were given a placebo and different doses of LSD (6.5, 13, and 26 μg). LSD tartrate was dissolved in water and administered sublingually–it was held under the tongue without swallowing for 60 seconds. The study used a within-subject, double-blind design, meaning each participant went through each drug/placebo condition and neither they nor the researchers were told what was given in each session.

They were told they may receive a placebo, sedative, stimulant, or hallucinogen during any given session.

Criteria for inclusion in the study:

- Criteria for participation (partial list): No current or past-year mental health disorders (as per the DSM-V list), no past year substance use disorder with alcohol or another drug, no medications aside from birth control, at least one prior psychedelic use (specifically with MDMA, LSD, psilocybin, or DMT ; case-by-case consideration of other psychedelics), and they could not have had an adverse reaction to a psychedelic adequate to make them unwilling to use one again.

- Drug use restrictions: Caffeine and nicotine were allowed before and after the session, but otherwise drug use was not permitted for 48 h before and 24 h after each session. Cannabis could not be used for 7 days prior and alcohol was not allowed for 24 before and 12 h after.

- Compliance with the drug use restrictions was confirmed using urinalysis and breath alcohol testing.

- Other: Participants could not drive, bike, or operate machinery for 12 h after a session.

Food:

- Subjects fasted for 12 h before a session and were given a granola bar upon arrival, then they received lunch 240 min after dosing.

Session Schedule and Environment

- Environment: Private lab rooms set up in a living room-like manner and containing computer for testing. Subjects relaxed, read, or watched movies in between tests.

- Administration: 9:30 am

- Subjective and cardiovascular measures: 10:30 am, 11:30 am, 1 pm, 2 pm, 3:30 pm, and 4:30 pm.

- Tasks measuring cognition and affective responses to stimuli were carried out at 12:00 pm, which was expected to be the peak.

- Follow-up: They completed a mood questionnaire 48 h after each session.

Demographics

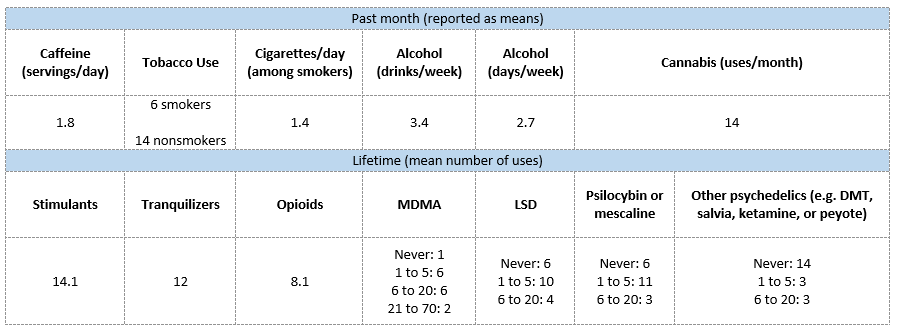

20 adults (12 females, 8 males) with a mean age of 25. They were psychologically healthy in terms of anxiety, depression, and stress scores on the DASS.

Drug use history:

Assessment Measures

Mood and Drug Effects

- Drug Effects Questionnaire (DEQ): Five questions in a Visual Analog Scale (VAS) style, specifically asking whether they feel a drug effect, like the effect, feel high, want more of what they are receiving, or dislike the effect.

- Addiction Researcher Center Inventory (ARCI): 49 true/false questions covering five subscales corresponding to specific effects from different drug classes.

- A (amphetamine-like; stimulant)

- BG (benzedrine-like; energy and intellectual efficiency)

- MBG (morphine-benzedrine-like; euphoria)

- LSD (psychedelic)

- PCAG (pentobarbital-chlorpromazine-alcohol; sedative)

- Profile of Mood States (POMS): Consists of 72 mood-related adjectives rated on a scale from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely). It is divided into subscales for anxiety, depression, anger, vigor, fatigue, confusion, friendliness, and elation.

- A version of the POMS depression scale was also given 48 h after each session to evaluate post-session mood effects.

- 5 Dimensions of Altered States of Consciousness (5D-ASC): Includes 94 statements intended to gauge a participant’s experience of sensations that commonly accompany psychedelic and mystical experiences. The statements cover five subscales: Oceanic Boundlessness, Dread of Ego Dissolution, Visionary Restructuralization, Acoustic Alterations, and Vigilance Reduction.

- Drug Identification: Participants guessed which drug they received.

Physiological, Behavioral, and Cognitive Effects

- Physiological: Heart rate (HR), systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), and body temperature.

- Working memory test: Dual N-back

- This assesses a subject’s ability to change their thinking to adapt to a new cognitive problem, a domain of cognition called fluid intelligence.

- They go through increasingly difficult trials during which they are shown shapes or letters for 3 seconds and then they must respond when they are shown the same item “n” number of stimuli in the future, in this case 2.

- Cognition: Digit Symbol Substitution Test (DDST)

- A common tool to test associative learning. It relies upon attention, response speed, and visual-spatial abilities.

- Subjects are given a key with 9 symbols corresponding to the numbers 1 through 9, then they are shown a series of numbers accompanied by blanks to enter the appropriate symbols. As fast as possible they must match the number to the correct symbol over a 90-sec period.

- Outcome measure: Number of correct symbols.

- Simulation of social exclusion: Cyberball test

- Subjects play a digital game of “catch” with two virtual players under two conditions: the acceptance phase and the rejection phase.

- Acceptance: They are included in the game, with ~60% of tosses directed at them.

- Rejection: They are excluded, with only ~15% of tosses directed at them.

- After those phases, they rate their mood and give an estimate for the % of tosses they received.

- Subjects play a digital game of “catch” with two virtual players under two conditions: the acceptance phase and the rejection phase.

- Emotional responses: Emotional Images Task

- Subjects rate images that are positively, negatively, and neutrally valenced.

- Creativity: Remote Associates Task (RAT)

- This measures a domain of creativity called convergent thinking and is commonly used to assess creative potential.

- Subjects are shown three words and then have 30 seconds to type in a fourth related word. There is only one “correct” answer for each word set, e.g. “girl” after being shown “flower,” “scout,” and “friend.”

- Outcome measure: The number of trials attempted and the number of correct responses out of 20.

Results

Subjective Effects

DEQ (significant effects vs. placebo)

- 6.5 μg: None

- 13 μg: Higher ratings of

- “feel drug” at 120 min and 240 min

- 26 μg: Higher ratings of

- “feel drug” at 120 min (p<0.001) and 240 min (p<0.01)

- “feel high” at 120 (p<0.001) and 180 min (p<0.001)

- “like drug effect” at 120 min (p<0.001)

- “dislike drug effect” at 240 min (p<0.05).

ARCI (significant effects vs. placebo)

- 6.5 μg: None

- 13 μg: None

- 26 μg: Higher ratings on

- “LSD” scale at 120 min (p<0.05) and 180 min (p<0.01)

- No dose significantly changed scores on the scales measuring stimulating, sedating, euphoric, or energizing/intellectual efficiency effects.

POMS (significant effects vs. placebo)

- 6.5 μg: None

- 13 μg: None

- 26 μg: Higher rating of vigor (p<0.05)

- Other

- Significant dose effect on “Friendliness” but it failed to reach significance during follow-up.

- Main effect of dose on “Anxiety,” with a trend towards the 26 μg dose raising that measure.

- No significant effect on: Elation, Depression, Anger, Fatigue, or Confusion.

5D-ASC (significant effects vs. placebo)

- 6.5 μg: None

- Dose-dependent increases on:

- Experience of Unity with 13 μg and 26 μg (both p<0.05)

- Blissful State with 13 μg (p<0.01) and 26 μg (p<0.05)

- Impaired Control and Cognition with 26 μg (p<0.05)

- Changed Meanings of Percepts (p<0.05)

- Other

- Trends towards increases on Spiritual Experience, Insightfulness, and Complex Imagery.

- No significant changes on: Disembodiment, Anxiety, Elementary Imagery, or Audiovisual Synesthesia.

Social Exclusion (Cyberball test)

- No significant effect.

Drug Identification

- While on placebo: 14 guessed placebo, 5 guessed sedative, and 1 guessed cannabinoid.

- While on 6.5 μg: 0 correctly guessed hallucinogen, 9 guessed placebo, 4 guessed stimulant, 4 guessed sedative, 1 guessed opioid, and 2 guessed cannabinoid.

- While on 13 μg: 2 correctly guessed hallucinogen, 9 guessed placebo, 3 guessed stimulant, 4 guessed sedative, and 1 guessed opioid.

- While on 26 μg: 6 correctly guessed hallucinogen, 6 guessed stimulant, 2 guessed sedative, 3 guessed cannabinoid, 1 guessed opioid, and 2 guessed placebo.

Follow-Up at 48 h

- 11/20 participants completed all four 48 h questionnaires. Based on their responses there was no significant effect on mood.

Cognitive

- Dual N-back: No significant effect of any dose.

- DSST: No significant effect of any dose.

Emotional and Creative Effects

- Emotional Images Task

- The only significant effect was a small decrease in positivity ratings when shown positive images at 26 μg.

- Remote Associates Task

- No significant effects and only a small non-significant increase in the number of attempted trials.

- Though it had almost no detectable effect on these tasks, LSD largely did not impair emotion recognition or creativity.

Physiological

- Systolic blood pressure

- 6.5 μg: No significant change

- 13 μg: Increase from 105.35 mmHg to 111.5 mmHg

- 26 μg: Increase from 105.35 mmHg to 115.3 mmHg

- Diastolic blood pressure

- 6.5 and 13 μg: No significant effect

- 26 μg: Significant increase

- No significant effect of any dose on heart rate or body temperature.

Conclusion

The results show LSD microdosing is associated with demonstrable changes in functioning. Small doses, particularly 13 and 26 μg, alter people’s subjective experience in a psychedelic-like manner, which is encouraging considering it may be a viable way to help people change how they view the world and interact with it. If there is a non-hallucinogenic way to produce effects like sensations of ‘unity,’ that could be very useful.

Even at the highest dose, participants had a difficult time guessing which drug they were given. An equal number said hallucinogen and stimulant, suggesting low doses have a vaguely defined ‘activating’ effect. That property could be especially prominent with LSD because microdosers often report it has a more stimulating effect than psilocybin and it is known to have a more promiscuous pharmacology than other psychedelics.

Considering the near absence of effects on emotional processing, it may be best not to try and learn much from the small negative effect observed with 26 μg LSD. The authors speculated it could be caused by LSD increasing connectivity between brain regions that are normally not as linked during certain tasks so that change could alter someone’s perception of emotionally charged stimuli for better or for worse. Hopefully this possibility will be explored in future research, but for now, there is not much to gain from a small measured effect.

This study did not support the popular claim that LSD microdosing enhances cognitive performance. On the tests used in this research, microdosing failed to improve indicators of learning ability and memory. Of course, more tests should be used and more people should be tested, but at the moment the idea that it should be grouped in with “nootropics” is not strongly supported; microdosing may end up showing the greatest efficacy in different areas. Instead of being a coffee or Adderall replacement, it could be a tool for improving mental health.

It is also important to see if people with a depressive or anxious baseline state respond differently to microdosing. The most glowing reports could conceivably be from people with mental health issues. If so, those effects would be difficult to detect in a small study of healthy people like this.

References

Anderson, T., Petranker, R., Rosenbaum, D., Weissman, C. R., Dinh-Williams, L.-A., Hui, K., … Farb, N. A. S. (2019). Microdosing psychedelics: personality, mental health, and creativity differences in microdosers. Psychopharmacology, 236(2), 731–740. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-018-5106-2

Bershad, A. K., Schepers, S. T., Bremmer, M. P., Lee, R., & de Wit, H. (2019). Acute Subjective and Behavioral Effects of Microdoses of Lysergic Acid Diethylamide in Healthy Human Volunteers. Biological Psychiatry, 86(10), 792–800. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2019.05.019

Cameron, L. P., Benson, C. J., DeFelice, B. C., Fiehn, O., & Olson, D. E. (2019). Chronic, Intermittent Microdoses of the Psychedelic N , N -Dimethyltryptamine (DMT) Produce Positive Effects on Mood and Anxiety in Rodents. ACS Chemical Neuroscience, 10(7), 3261–3270. https://doi.org/10.1021/acschemneuro.8b00692

Horsley, R. R., Páleníček, T., Kolin, J., & Valeš, K. (2018). Psilocin and ketamine microdosing. Behavioural Pharmacology, 29(6), 1. https://doi.org/10.1097/FBP.0000000000000394

Johnstad, P. G. (2018). Powerful substances in tiny amounts. Nordic Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 35(1), 39–51. https://doi.org/10.1177/1455072517753339

Polito, V., & Stevenson, R. J. (2019). A systematic study of microdosing psychedelics. PLOS ONE, 14(2), e0211023. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0211023

Prochazkova, L., Lippelt, D. P., Colzato, L. S., Kuchar, M., Sjoerds, Z., & Hommel, B. (2018). Exploring the effect of microdosing psychedelics on creativity in an open-label natural setting. Psychopharmacology, 235(12), 3401–3413. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-018-5049-7

Yanakieva, S., Polychroni, N., Family, N., Williams, L. T. J., Luke, D. P., & Terhune, D. B. (2019). The effects of microdose LSD on time perception: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Psychopharmacology, 236(4), 1159–1170. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-018-5119-x