Methaqualone is a sedative that falls outside the benzodiazepine and barbiturate classes. It was once a popular pharmaceutical and recreational drug, but its current use is largely relegated to Africa, particularly South Africa.

Because it faced few restrictions when it first entered the market, the drug was widely prescribed and perceived as uniquely safe. We now know methaqualone can be used recreationally and can cause physical dependence.

A lot of lore exists around the effects. In reality, it’s not a massively unique substance and it can be compared to barbiturates, ethanol, carisoprodol, and meprobamate.

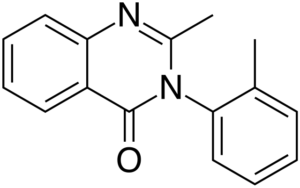

Methaqualone = Quaalude; Mandrax; 2-methyl-3-(2-methylphenyl)-4(3H)-quinazolinone; Sopor; Metolquizolone; Metaqualon; Ortonal; Cateudyl; Melsomin; Melsedin; Parest

PubChem: 6292

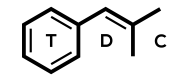

Molecular formula: C16H14N2O

Molecular weight: 250.301 g/mol

IUPAC: 2-methyl-3-(2-methylphenyl)quinazolin-4-one

Contents

Dose

Oral

Medical

- Daytime sedation/anxiolysis: 75 mg up to 3-4x daily

- Sleep: 150 – 400 mg

Recreational

- Light: 150 – 300 mg

- Common: 300 – 600 mg

- Strong: 600+ mg

Timeline

Oral

Total (medical): 6 – 8 hours

Total (recreational): 4 – 6 hours

Onset: ~00:30

The core recreational effects persist for about 6 hours, but some sedation and impairment can last beyond that point.

Experience Reports

Effects

Positive

- Sedation

- Anxiolysis

- Euphoria

- Pleasant tingling sensations

- Pro-sexual effects

- Disinhibition

Negative

- Headache

- Dizziness

- Restlessness

- Dry mouth

- Slurred speech

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Diarrhea

- Sweating

- Reduced HR and BP

- Unconsciousness

Core effects

The two primary effects of methaqualone are euphoria and sedation. It can offer notable levels of euphoria without overwhelming sedation, which sometimes makes it preferable to barbiturates. Some people find you must fight off an urge to sleep, while others easily remain awake at common doses.

When it does produce strong sedation, that effect can often dissipate within a couple hours.

At common doses, a form of mental energy/stimulation is fairly common. This either occurs without any mental sedation or after a short period of sedation. During this time, the body is relaxed/sedated.

It can reduce your inhibitions, which comes with positive and negative potentials. There’s a higher likelihood of unsafe or inappropriate behavior.

Paresthesia of the legs, arms, fingers, lips, and tongue is common with recreational amounts.

Users will feel somewhat like they’re drunk. This is due to staggering from impaired motor control and because of their improved, disinhibited mood.

Your body tends to feel loose, relaxed, and it may feel warm.

Especially with higher doses, talking can be more difficult as a result of slurring.

Throughout its history it has been combined with ethanol and other depressants to boost the effects. This isn’t a good idea.

Comparison to other drugs

Some comparisons can be made to other depressants with significant recreational potential. That would include drugs like ethanol, barbiturates, carisoprodol, and meprobamate.

It’s more euphoric and recreational overall than benzodiazepines.

The substance stands out from other depressants in that it’s pretty efficacious as an antispasmodic, though it’s not the only kind of depressant with that property. It also has some antitussive effects.

Modern use

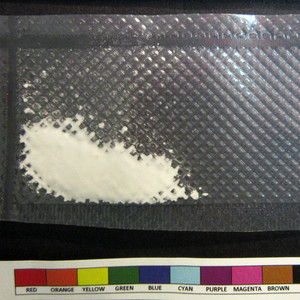

It’s still used in a handful of regions, most notably South Africa. In this area, inhalation is common.

By taking the drug via that route instead of orally, a greater “rush” of sedation, relaxation, and euphoria may be produced. Though it can also rapidly impair motor control, which can be dangerous.

Lore

Methaqualone was widely described as a strong aphrodisiac beginning in the 1960s and 1970s. Some users referred to it as a “love drug,” claiming it could drastically boost sexual desire. It’s still remembered as offering those effects, which have been highlighted in movies (e.g. The Wolf of Wall Street) and the media.

At the very least, it’s fair to say the drug can alter interpersonal relationships due to anxiolysis and disinhibition. This by itself can lead to a form of “aphrodisia.”

But it’s important to understand a large portion of the alleged aphrodisia is likely context-dependent. A dose the produces aphrodisia when used by sexual partners could be fully void of that effect when used medically for sleep. As such, disinhibition leads to different effects based on the situation.

Expectancies regarding its alleged pro-sexual activity could have also led to its reputation.

Papers

(Claus, 1980) – In rhesus monkeys, it produced some effects on sexual behavior, such as increased autoeroticism and general sexual activity.

(Gerald, 1973)

- Survey of human users.

- Compared anticipated effects to those actually experienced under the drug.

- Percent who actually experienced increased libido, bodily sensations, paresthesia, and a desire to have sexual intercourse was substantially higher than the percent who only anticipated those effects.

- This offers tentative support for pro-sexual qualities.

(Kochanasky, 1975) – Survey of users found the drug offers distinct increases in sexual arousal.

Medicine

It was primarily used for insomnia and to a lesser extent for anxiolysis and other forms of sedation.

Insomnia/sleep

(Ravina, 1959)

- Used 150 mg orally

- 54/100 patients found the hypnotic effects were superior to other hypnotics. No placebo was used, however.

(Parsons, 1961 — UK)

- Comparing methaqualone with cyclobarbitone, with placebo pills also used in some of the trials.

- 100 total patients (79 females)

- Patients evaluated by self-reporting of sleep quality.

- Results

- 150 mg of methaqualone was superior to placebo.

- 11/28 found “no difference.”

- 150 mg of methaqualone wasn’t notably different from 200 mg of cyclobarbitone

- 13/43 found no difference between the treatments

- During this trial, 3 patients said methaqualone made them restless before they fell asleep. Those individuals preferred cyclobarbitone.

- Only 1 patient complained of restlessness after cyclobarbitone.

- 300 mg of methaqualone was superior to 200 mg of cyclobarbitone

- 150 mg of methaqualone was superior to placebo.

- COI: Only tablets provided by Boots Pure Drug Company.

(Goldstein, 1970 – US)

- 10 adults

- Methaqualone 300 mg vs. glutethimide 500 mg

- Single blind

- 1-3 night with placebo, then 4-6 night with drug, then 7-10 night with placebo

- Results

- Decreased wakefulness with glutethimide during drug nights. However, not significant. Stage 2 increased significantly during drug nights and returned to control levels during recovery. Stage 3 and 4 weren’t significantly changed during drug nights or recovery. State REM declined non-significantly during drug.

- During recovery nights, REM increased markedly, becoming highly significant vs drug nights and recovery nights.

- Methaqualone

- Significant decline in wakefulness. During recovery nights, there was a rise in wakefulness, though not returning to predrug values.

- Stage 2 increased during drug nights. Returned to control levels during recovery.

- No Stage 3 change.

- Stage 4: Significant decline during drug nights that persisted during recovery.

- Duration of stage REM didn’t change during drug nights, but significant rise above control during recovery.

- Latency to first REM increased during drug nights for both. But non-significant with methaqualone, while significant with glutethimide.

- Mean number of REM periods: No significant change during drug and/or recovery nights.

- Decreased wakefulness with glutethimide during drug nights. However, not significant. Stage 2 increased significantly during drug nights and returned to control levels during recovery. Stage 3 and 4 weren’t significantly changed during drug nights or recovery. State REM declined non-significantly during drug.

- COI: “This study was supported by a grant from William H. Rorer, Inc., Fort Washington, Pa. 19034.”

(Barcelo, 1961 – Canada)

- 105 hospitalized patients

- 150 mg of methaqualone vs. 100 mg of secobarbital vs. placebo

- All had been receiving hypnotics for sleep. Drug administered in the study changed every 5 days. All three preparations were given to 28 people; 40 received just two; and 37 received just one

- Results

- Significant difference between placebo and the drugs.

- 38% for placebo slept “excellent,” compared with 74% for methaqualone and 81% for secobarbital.

- For “poor” sleep, that was seen with 72% for placebo, 20% for methaqualone, and 8% for secobarbital.

- Side effects

- Fatigue, drowsiness, heaviness, and headache seen in 35 cases. 40% reported by placebo, 37% after secobarbital, and 23% after methaqualone.

(Duchastel, 1962 – Canada)

- 100 patients; double-blind

- Given 30 min before sleep. Patients received methaqualone or placebo for a week and then switched.

- Results

- Had a good sedative effect, comparable with that of other barbiturate and non-barbiturate hypnotics.

- 72 patients receiving methaqualone had distinctly better results than placebo group. 87% reported excellent or very good results, compared to 46% with placebo.

- Based on a smaller 10 patient study in people with anxiety, it was found not to have much of a tranquilizing effect at 75 mg 4x per day.

- Had a good sedative effect, comparable with that of other barbiturate and non-barbiturate hypnotics.

- COI: Rougier Inc. supplied the product.

(Taverner, 1962 – UK)

- 24 participants

- All were inpatients, half in the acute psychiatric unit.

- Participants told they would be given pills that may “make them want to go to sleep.”

- Sleeping reports gathered every 15 min for 4 hours, leading to a total point system of 16. (Sleeping=Point; Not=No)

- Dose

- Methaqualone: 150 or 300 mg

- Cyclobarbital: 200 or 400 mg

- Results

- 150 mg of methaqualone vs. 200 mg of cyclobarbital

- 52 sleep reports for methaqualone; 57 sleep reports for cyclobarbital

- Not a significant difference.

- 300 mg of methaqualone vs. 400 mg of cyclobarbital

- 111 sleep reports for methaqualone; 40 sleep reports for cyclobarbital

- Significant difference.

- 150 mg of methaqualone vs. 200 mg of cyclobarbital

- Interpretation

- There’s a significantly greater beneficial effect of methaqualone at 300 mg than from 400 mg of cyclobarbital, the maximum recommended dose.

- And there’s also a significantly greater effect from 300 vs. 150 mg of methaqualone, whereas the sleep-induction of cyclobarbital wasn’t significantly dose-dependent.

- COI: Boots Pure Drug provided the product.

(Risberg, 1975 – Sweden)

- 10 healthy people, not individuals with insomnia.

- Comparing methaqualone at 250 mg with dixyrazine at 25/50 mg, and isonox (methaqualone 250 mg + etidroxizine 50 mg)

- Results

- Single doses

- REM percent under placebo: 23.3%

- REM sleep declined to 21.3% with methaqualone. But the decline in REM was pretty minor.

- Significant rise in Stage 2 sleep from methaqualone.

- Only with acute use. No significant changes on any sleep architecture measure with 32 total nights (8 baseline, 12 drug, and 12 withdrawal)

- Number of REM periods

- No significant change.

- Eye movement during REM

- While dixyrazine insignificantly increased movement frequency, methaqualone (p<0.01) and isonox (p<0.05) significantly decreased eye movement frequency.

- REM latency

- Didn’t significantly alter. Latency and time awake during the night were insignificantly declined under all drugs.

- Sleep quality generally reported as “very good.”

- Morning drowsiness

- Dixyrazine 25 mg and methaqualone didn’t produce drowsiness or muscle incoordination, unlike dixyrazine 50 mg and Isonox

- Repeated doses

- Initial decline in REM % during the first night, but the decrease went away after that acute use, followed by increases (up to 25%).

- Overall, the REM % values were always pretty close to baseline.

- Initial decline in REM % during the first night, but the decrease went away after that acute use, followed by increases (up to 25%).

- Single doses

Surgery anesthesia

(Saxena, 1972 – India)

- 40 people undergoing ear/nose/throat surgery or general surgery

- Either single IV 5 mg/kg dose or 300 mg IV or IV 200 mg (2-3x)

- Results

- Consciousness was lost almost immediately after an adequate IV dose.

- Transient generalized muscle spasms followed the onset of sleep; only lasted about a minute.

- Followed by muscular relaxation.

- No marked changes in BP or HR during induction or maintenance.

- After 5 mg/kg IV, consciousness began to return in about 10-15 min.

Preoperative sedation

(Norris, 1966 – Scotland)

- 96 total patients: 48 receiving Mandrax and 48 receiving placebo

- All were going through minor gynecological procedures.

- Results

- Sedation

- Mandrax led to significantly more “good” sedation responses than placebo.

- Mean sedation score with Mandrax was significantly higher. Results ended up similar to those with a combo of papaveretum (20 mg)/hyoscine (0.4 mg) and with heptabarbitone (400 mg)

- Mandrax was shown to be effective in offering sedation for up to 5 hours.

- Side effects

- Minimal differences in heart rate and blood pressure

- Incidence of nausea and vomiting is similar. Also similar for dry mouth preoperatively.

- Sedation

Non-medical papers

(Jasinski) – Two studies involving prisoner addict volunteers.

- Comparing methaqualone (100, 160, 200, 320, and 400 mg) with pentobarbital (50, 100, and 200 mg)

- Found methaqualone was 1.5 to 4x less potent; similar duration of action and onset.

- Under double-blind conditions, it led to sedative and euphoric effects characteristic of barbiturates.

- It did, however, result in parasthesias not seen with pentobarbital.

(Ionescu-Pioggia, 1988)

- 24 subjects

- Each received all 3 conditions: 200 and 400 mg methaqualone, and placebo.

- Results

- Methaqualone is discriminable from placebo on almost every ARCI scale.

- Euphoria

- 200 mg and 400 mg led to nearly identical average effects.

- Sedation

- 400 mg tended to be significantly more sedative than 200 mg.

- At 2 and 3 hours post-drug, all conditions are significantly different from each other.

- Interpretation

- Supports the dose-dependency of sedation and relative lack of dose-dependency for euphoria.

(Orzack, 1988 – US) – Study comparing the recreational effects of benzodiazepines, methaqualone, and placebo.

- 30 recreational drug users recruited from college population.

- Prior drug use during the past 30 days (mean use)

- Alcohol: 8.3

- Cannabis: 8.4

- Barbiturates: 0.2

- Methaqualone: 0.2

- Benzodiazepines: 0.5

- Prior drug use during the past 30 days (mean use)

- Results

- Euphoria

- At 1 hour, methaqualone leads to significantly more euphoria than alprazolam or placebo.

- Diazepam and lorazepam are more euphoriant than placebo but are not significantly less than methaqualone.

- Sedation

- At 1 hour, only diazepam is more sedating than methaqualone. And alprazolam is more sedating than placebo.

- Sedation from lorazepam and alprazolam increases during the session, remaining significantly different from methaqualone except at Hour 3.

- Diazepam and alprazolam differ consistently from placebo.

- Mental sedation

- At 1 hour, the benzodiazepines are equally sedating and differ significantly from placebo. Diazepam alone is more sedating than methaqualone.

- Alprazolam and lorazepam become increasingly more effective, and at Hours 2 and 4, all three benzodiazepines are more mentally sedating than either methaqualone or placebo.

- Physical sedation

- At 1 hour, all treatments differ initially from placebo, but not from each other.

- Methaqualone becomes less sedating and by Hour 3, all benzodiazepines cause more sedation than methaqualone and placebo.

- At 4 hours, lorazepam and alprazolam alone are more physically sedating than placebo and methaqualone.

- Sedative intoxication (feeling of intoxication without being drunk)

- All treatments are initially equipotent.

- At 2 hours, only the benzodiazepines are equally effective and significantly different from placebo.

- At 3 hours, lorazepam becomes the most sedating, differing significantly from diazepam and methaqualone.

- At this point, alprazolam is also highly sedating, but less so than lorazepam.

- At 4 hours, lorazepam and alprazolam are more sedating than methaqualone but not more so than diazepam.

- Participants judged methaqualone to be worth the most money and diazepam to be the next most valuable.

- Only the values for methaqualone and diazepam were significantly different from placebo; the former differed significantly from all other treatments.

- Participants indicated they would tend to use all drugs again, but methaqualone was considered significantly more likely to be used than lorazepam and alprazolam, but not diazepam. All treatments differed significantly from placebo.

- Global rating of physical or mental “high”

- Lorazepam and alprazolam were regularly close, but generally lower than diazepam. Differences among benzodiazepines was never significant.

- Methaqualone was always the highest on these ratings, sometimes significantly more than benzodiazepines.

- Euphoria

- Interpretation

- Methaqualone is more euphoric than any other drug tested. And the sedation declines to a greater degree faster.

- COI

- “This research was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (DA-02349) awarded to J. 0. Cole, and by a grant from the Upjohn Corporation, Kalamazoo, Michigan.”

(Slak, 1985 – US) – Case report involving long-term use.

- Case of someone using the drug recreationally for 14 years

- 35-year-old male; took it from 1970 to 1984

- Minimum daily dose of 240 mg; max dose of 2400 mg in divided doses

- Drug had been obtained for insomnia, but it was used to receive euphoria during the day.

- Euphoria would arrive in 30-45 min. Often used alongside alcohol.

- Effects: tingling sensations in the extremities, numbness, feeling of arousal, social disinhibition, and moderate sexual arousal.

- At higher doses: slurred speech, tremors, disoriented thinking, memory impairment, irrational acts, and sometimes vomiting.

- Withdrawal: insomnia during the first night only, agitation, irritability, bad temper, and low mood for 5-6 days at decreasing intensity, oily skin, moderate tachycardia.

- Said methaqualone was more effective, as both a hypnotic and euphoriant, than barbiturates like secobarbital or amobarbital. And had fewer side effects.

- Said it was superior in both ways to triazolam.

Animal studies

(Soulairac, 1967 – France)

- Rats

- Methaqualone at 100 mg/kg (oral) led to sleep in which phases of SWS alternate with paradoxical sleep.

- The paradoxical phases aren’t accompanied by the usual activation of the cortical trace, though the mesencephalic reticular formation doesn’t show abnormal modifications of excitability.

- It appears the action of methaqualone isn’t due to a direct activity on the mesencephalic reticular formation, thus making it very clearly different from barbiturates.

(Boggan, 1977) – Effect on seizure susceptibility in mice

- Background

- It’s been shown to potently protect against pentylenetetrazol and electroshock seizures in animals.

- Mice given 25, 50, and 75 mg/kg IP

- Results

- Dose-dependent protection against convulsions induced electrically, by pentylenetetrazol, and by sound. Effect is seen by 0.25 hours and lasts for at least 4 hours against ECS/pentylenetetrazol and for 8 hours against sound.

- Incidence of wild running, tonic convulsions, and death mimic data for clonic convulsions.

- Incidence of spasms after ECS or pentylenetetrazol wasn’t changed.

- Pretreatment with SKF525A, a liver enzyme metabolism blocker, didn’t impact efficacy.

- Tolerance

- When given at 75 mg/kg for 6 days, tolerance developed to the anticonvulsant effect, with the last dose being less effective in the chronically treated animal.

- Dose-dependent protection against convulsions induced electrically, by pentylenetetrazol, and by sound. Effect is seen by 0.25 hours and lasts for at least 4 hours against ECS/pentylenetetrazol and for 8 hours against sound.

- COI: “This research was supported by National Institute of Drug Abuse Grant DA01035 to W.O.B. and by General Research Support Grant RR05420 from NIH to the Medical University of South Carolina and J.S.M. Methaqualone was generously provided by William H. Rorer, Inc., Fort Washington, Pennsylvania. The technical assistance of Ms. Peggy Hendricks, Mrs. David Hopkins, and Mr. Jim Gardner is gratefully acknowledged.”

Chemistry & Pharmacology

Chemistry

Methaqualone is a quinazolinone derivative. It isn’t part of the typical depressant categories.

Pharmacology

Although some early research indicated it may operate at the benzodiazepine receptor site, this doesn’t appear to be the case. More recent evaluations have pointed to a different GABAA modulatory site located on the transmembrane b(+)/a(-) subunit interface.

It seems to bind in a similar way to etomidate, an anesthetic. And there’s a specific region of the beta subunit of GABAA receptor complexes that’s important for its properties.

Most of its activity comes from its nature as a positive allosteric modulator (PAM), meaning it alters GABA’s activity (i.e. increases in the generated chloride currents.) Some minor agonism is also present, but it’s not comparatively significant.

Papers

(Muller, 1978) – Potent inhibitor of diazepam binding in rat brain synaptosomal membranes, indicating it can bind to the benzodiazepine receptor site.

(Hammer, 2015)

- Background

- Hypothesized to act through GABAA receptors for years, but we didn’t know how. Benzo site? Neurosteroid site? Barbiturate site?

- The GABAA receptor complex is made of many subunits and also has multiple allosteric sites.

- Study

- Looked primarily at human GABAA receptor subtypes expressed in Xenopus oocytes.

- Also some animal studies and other in vitro research.

- Results

- Functional characterization of methaqualone at human GABAA receptor complexes expressed in Xenopus oocytes

- Properties determined at a1b2y2s, a2b2y2s, a3b2y2s, a4b2delta, a5b2y2s, and a6b2delta

- Agonism

- Negligible at a1,2,3,5b2y2s receptors (1-4% of GABA)

- Slightly more at a4b2delta (5.5% of GABA)

- More at a6b2delta (13% of GABA)

- Outside of being a small intrinsic agonist, methaqualone operated as a PAM, exhibiting mid-micromolar EC50 values at all six receptors when coapplied with GABA EC10.

- Potentiation of GABA (EC10)-evoked currents by methaqualone

- a1b2y2s, a2b2y2s, a3b2y2s, and a5b2y2s

- Currents were potentiated 6 to 8-fold at the maximum efficacy concentration of methaqualone.

- a4b2delta and a6b2delta

- a1b2y2s, a2b2y2s, a3b2y2s, and a5b2y2s

- Even greater effect; potentiating the current amplitude to 2- to 3-fold greater than the maximal response from GABA itself.

- There were pronounced rebound currents at methaqualone concentrations over 300 uM vs. 1 – 200 uM.

- a6b2delta

- GABA concentrations (low) that couldn’t evoke significant currents were able to induce substantial currents when 300 uM methaqualone was also used.

- Importance of the beta subunit and accessory y2s and delta subunits

- Potentiation at a1bY2s receptors didn’t appear dependent on y2s since the functionalities barely differed at a1b2 receptors.

- And, substituting b2 for b3 in the a1bY2s complex didn’t significantly alter the potency or efficacy of methaqualone as a PAM.

- However, it had dramatically different effects at the different B subunit containing a4bdelta and a6bdelta subtypes.

- Methaqualone didn’t modulate responses from GABA (EC10 or EC70) in the a4b1delta subtype

- Whereas with a4b3delta, methaqualone become a superagonist with an efficacy akin to the orthosteric agonist THIP (gaboxadol).

- Methaqualone was less efficacious as a PAM at a6b3delta than at a6b2delta

- And it actually functioned as a weak NAM at a6b1delta.

- Delineation of the mechanism of action of methaqualone at GABAA

- Benzodiazepine site

- Experiment 1

- As expected, flumazenil (10 uM) didn’t itself alter GABA EC10 activity. But, it fully blocked the potentiation of GABA EC10 by diazepam (3 uM)

- For methaqualone, flumazenil (10 uM) didn’t reduce the potentiation at a1b2y2s receptors.

- Experiment 2

- Investigating impact of a1-H102R mutation

- Substitution of that conserved histidine residue in the a1,2,3,5-subunit with an arginine has been shown to make a1,2,3,5bY receptors insensitive to benzodiazepines.

- With this mutation, diazepam (3 uM) was totally inactive as a PAM for modified a1b2y2s receptors.

- Yet, the activity of methaqualone (300 uM) didn’t substantially differ.

- Investigating impact of a1-H102R mutation

- Appears the benzodiazepine site isn’t the site for methaqualone.

- Experiment 1

- Barbiturate site

- Exact location of barbiturate binding still hasn’t been identified.

- At a1b2y2s, current amplitudes elicited by 300 uM methaqualone (1.2%) and by 300 uM pentobarbital (4.9%) were significantly smaller than if they were coapplied (18%).

- The ability of methaqualone to potentiate pentobarbital-evoked a1b2y2s signaling demonstrates it binds to a site that doesn’t overlap with the barbiturate binding site.

- Neurosteroid site

- Two binding sites for neurosteroids in the transmembrane domains of murine a1b2y2 GABAA receptors have been proposed

- Intersubunit site at the b(+)/a(-) subunit interface, which comprises the a1-TM1 residue Thr236

- Said to be important for neurosteroid activation (agonist activity)

- Intrasubunit site in the a subunit, comprising the a1-TM1 residue Gln241

- Intersubunit site at the b(+)/a(-) subunit interface, which comprises the a1-TM1 residue Thr236

- Two binding sites for neurosteroids in the transmembrane domains of murine a1b2y2 GABAA receptors have been proposed

- Benzodiazepine site

- Said to be important for neurosteroid potentiation (PAM) and activation (agonism)

- Studied the impact of mutations at both sites (Thr237 and Gln242)

- Methaqualone (300 uM) potentiation of GABA EC10 at a1b2y2s wasn’t significantly changed by the introduction of either mutation at the a1 subunit.

- Although we need to learn more, the lack of impact on its potentiation suggests methaqualone isn’t functioning through the primary GABAA neurosteroid sites.

- Transmembrane b(+)/a(-) subunit interface

- This subunit interface has multiple binding sites for allosteric modulators, though outside of the site for etomidate, we don’t know much about the compositions and locations of the binding regions.

- Several modulators also exhibit selectivity between GABAA receptor subtypes based on their respective B-subunits

- So, the activity of methaqualone at different B-subunit containing a4bdelta and a6bdelta receptors was investigated, specifically looking at the importance of three transmembrane residues.

- Residue 265 in TM2 of the beta subunit is a key molecular determinant of the B-selectivity of multiple interface modulators

- This isn’t believed to play a role in etomidate binding. Instead, it operates as a transduction element between modulator binding and its effect on gating.

- For etomidate, introduction the N265M mutation in b2 eliminated etomidate’s potentiation of a1b2y2s signaling.

- Interestingly, that mutation also had a detrimental effect on methaqualone’s activity.

- Also, the PAM and NAM activites of methaqualone (PAM at a6b2delta and NAM at a6b1delta) were fully reversed by introducing the reciprocal residue in position 265 of the respective b subunits.

- Methaqualone become roughly equipotent and equally efficacious as a PAM at regular a6b2delta and modified a6b1delta

- And was also basically the same for NAM activity at regular a6b1delta and modified a6b2delta

- Studies have also demonstrated the importance of a1-TM1 Met236 and b2-TM3 Met286 residues for GABAA modulation by etomidate

- Those residues are believed to form direct interactions with the modulator.

- Etomidate had greater intrinsic activity at a1(m236w)b2y2s that at the wild-type receptor

- Yet it was totally inactive at a1b2(m286w)y2s receptor

- Similarly, the insignificant agonism of methaqualone at wild-type a1b2y2s became pronounced agonism at a1(m236w)b2y2s receptor

- The impact of the b2-m286w mutation was more subtle than it was for etomidate

- Methaqualone remained roughly equipotent but less efficacious as a PAM for a1b2(m286w)y2s receptor compared to wild-type.

- Etomidate is a fairly pure PAM at a4b2delta and a superagonist at a4b3delta (similar to methaqualone)

- But, it has PAM activity at a4b1delta, while methaqualone (up to 300 uM) is inactive at that receptor subtype.

- Putative binding modes of etomidate, loreclezole, and methaqualone

- Overall, these results suggest methaqualone is operating through the same transmembrane b(+)/a(-) subunit interface in the GABAA complex as etomidate, loreclezole (anticonvulsant), and other modulators.

- Structural similarities between the drugs that could be important.

- Etomidate and methaqualone

- Have two hydrophobic moieties, a carbonyl group, and an aromatic nitrogen capable of acting as a hydrogen bond acceptor.

- Etomidate and methaqualone

- Screening of methaqualone at other putative CNS targets

- PDSP screening of 50 recombinant neurotransmitter receptors and transporters, and at native GABAA receptors and ionotropic glutamate receptors in rat brain homogenates.

- Methaqualone (30 uM) failed to display significant modulation (potentiation or inhibition) of radioligand binding at all sites.

- It was also inactive at up to 1 mM when tested in functional assays at other plasma membrane-bound targets for GABA (GABAB receptors and GABA transporters)

- Methaqualone (30 uM) didn’t compete with muscimol or flunitrazepam binding in rat brain.

- This is unlike etomidate and loreclezole, which can enhance the binding of both.

- Multiparametric description of the effects of methaqualone on cortical network activity in vitro

- Using murine frontal cortex grown on MEA neurochips

- Looking for changes in neuronal network activity

- Concentration-effect relationships for methaqualone and other GABAA modulators in the network recordings

- Overall profile of the drug was characteristic for a CNS depressant.

- Significantly reduced spike and burst rates and increased the interval between bursts as well as the average burst period (at 1 – 100 uM).

- Burst sizes were significantly reduced by methaqualone (decreased burst duration, burst area, and burst amplitude)

- Also an increase in network variability

- Indicative of decreased synchronization within the network.

- Multiparametric effects from methaqualone were quite similar to those from diazepam, etomidate, and phenobarbital.

- Using murine frontal cortex grown on MEA neurochips

- Though there were some interesting differences.

- High or saturating levels of etomidate or methaqualone led to more pronounced changes in some “general activity,” “burst structure,” and “oscillatory behavior” parameters vs. high/saturating levels of phenobarbital or diazepam.

- Though there were some interesting differences.

- Similarity analysis and classification

- With the exception of chlorpromazine and amitriptyline, the database compounds with the greatest similarities to methaqualone were GABAA PAMs (etomidate, diazepam, thiopental), NMDA antagonists (MK-801, memantine), and other CNS depressants (valproate, retigabine.)

- In vivo tests on seizure threshold and motor coordination

- Plasma and brain concentrations following SC administration peaked at 60 minutes (from 10 mg/kg in mice)

- Concentrations from different doses

- Plasma

- 10 mg/kg – 2.79 ug/mL

- 30 mg/kg – 12.3 ug/mL

- 100 mg/kg – 26.7 ug/mL

- Brain

- 10 mg/kg – 0.71 ug/g

- 30 mg/kg – 4.1 ug/g

- 100 mg/kg – 16.1 ug/g

- Plasma

- Functional characterization of methaqualone at human GABAA receptor complexes expressed in Xenopus oocytes

- Seizure threshold

- SC 100 mg/kg significantly increased seizure threshold in mice with the MEST assay.

- Motor

- SC 30 and 100 mg/kg significantly increased the number of slips and falls in the beam-walk assay

- Seizure threshold

- Interpretation

- Methaqualone is a multifacted GABAA modulator

- It’s active at 12 of 13 GABAA subtypes tested

- Though typically a pure PAM, it also has instances of inactivity (or silent allosteric modulator), negative modulation, and pronounced agonism.

- The comparable functional potencies as a PAM, NAM, or agonist at the various subtypes suggests methaqualone is targeting a uniform binding site in the receptors.

- Further supported by the reversal of modulation at a6b1delta and a6b2delta by b1-s265n and b2-n265s mutations

- Submaximal potentiation seen at high modulator concentrations may come from the existence of a low-affinity open-channel block site, with the rebound currents arising from the rapid unbinding of the modulator (i.e. methaqualone) from that site.

- However, the submaximal potentiation at high concentrations could also come from increased receptor desensitization.

- The methaqualone binding site

- Good evidence for it not operating through benzodiazepine, barbiturate, or neurosteroid sites.

- Appears the b-subunit identity is very important; namely the b-residue 265

- So, there’s a strong case to be made for the transmembrane b(+)/a(-) interface being the targeted receptor region.

- Functional characteristic of methaqualone at cortical neurons

- Overall, the effects on neuronal firing patterns in cortical networks fits with GABAA activity.

- And its activity is akin to other GABAA PAMs, NMDA antagonists, and other known CNS depressants vs. alternative drugs.

- Methaqualone is a multifacted GABAA modulator

EEG

(Pfeiffer, 1968 – United States)

- Studying the EEG effects in humans; looking at mean energy content (MEC) and coefficient of variation (CV)

- 17 volunteers

- Electrodes applied early in the morning

- Doses: 37.5 mg, 75 mg, 150 mg, 225 mg, and 300 mg.

- Results

- Significant decreased in MEC after the 4th hour following 75 mg, but non-significant.

- Most significant changes at 300 mg

- Significant rise in MEC at all hours after dosing for the males; CV was significantly larger at the 1st and 2nd hours.

- 300 mg EEG effects are similar, but not identical with, spontaneous drowsiness.

- The EEG effects of hypnotic doses differ from pentobarbital and glutethimide.

Pharmacokinetics

Tmax: 2 hours

Half-life: ~4 hours (though often listed as 10-40 hours)

Papers

(Clifford, 1974 — England)

- Healthy males. For each drug, there were two experiments at least 14 days apart.

- Comparing the PK of methaqualone, secobarbital, and heptabarbital; all given orally

- Methaqualone

- 300 mg was given to 7 male subjects

- Mean plasma levels:

- 2 hours: 1.76 ug/mL

- 2.5 hours: 1.90 ug/mL

- 3 hours: 2.12 ug/mL

- 3.5 hours: 1.73 ug/mL

- 4 hours: 1.22 ug/mL

- 6 hours: 1.12 ug/mL

- Mean Tmax was around the third hour.

- Estimated that 90% of absorption occurred by ~2 hours.

- Compared to the two barbiturates, only nanogram amounts of methaqualone and ethinamate were found in plasma at 10 hours post-dose, suggesting lower chance of residual effects.

Impact of diphenhydramine

Mandrax (methaqualone-diphenhydramine) may have had superior efficacy as a hypnotic due to the combined depressant actions of the drugs. But potential pharmacokinetic interactions weren’t fully investigated, so the full nature of their combined effects isn’t known.

Papers

(Williams, 1974 – UK)

- 3 volunteers

- No significant difference between methaqualone-only and methaqualone-diphenhydramine on Cmax or Tmax, indicating a lack of impact on the oral absorption of methaqualone.

(Gupta, 1982 – India) – Possible impact of diphenhydramine on the PK of methaqualone

- Rats

- Either combining them or pretreating for 20 days with diphenhydramine

- Results

- Controls: Half-life was 2.32 hours

- Diphenhydramine combo led to a 54% drop in elimination rate constant and 57% drop in metabolic clearance rate, leading to 116% increase in biological half-life.

- However, chronic treatment for 20 days (with no diphenhydramine for 14 to 16 hours before methaqualone) had no impact.

- Diphenhydramine may inhibit MFO catalysed methaqualone biotransformation. Supported by an earlier study where diphenhydramine caused an appreciable decline in the rate of in vitro biotransformation of methaqualone to a major inactive metabolite in liver fraction.

History

1950s

Methaqualone was synthesized in India in 1951. It was originally developed as part of a program looking for antimalarial substances.

While it didn’t have antimalarial properties, methaqualone was found to be a hypnotic by 1955. And a pharmacological study in 1957 confirmed it was the most active drug out of the group synthesized.

Early tests completed at King George’s Medical College in India found its hypnotic potency was greater than phenobarbital in rats and it also led to a greater duration and soundness of sleep (Gujral, 1955).

1950s and 1960s

Along with clinical investigations supporting methaqualone’s hypnotic effects, other trials found it could have applications beyond insomnia.

(Saxena, 1967) – It effectively abolished muscular spasms and induced a deep hypnosis in those with tetanus. These effects were seen in 5 – 10 min after receiving 200 to 400 mg (IM). The benefits lasted around 2 hours.

It could increase the analgesic effect of codeine in animals.

For insomnia, investigations were carried out by Ravina in France (1959), by Cass in the US (1959), and by Parsons in the UK (1961).

Early researchers liked the drug because it appeared to have barbiturate-like sedative/hypnotic effects, yet it was seemingly safer in overdose.

1960s – Early medical and nonmedical history outside of the US

Before the drug had a notable history in the United States, it was widely used in medicine and for recreational purposes elsewhere. Reports of nonnmedical use and dependence in the UK, Japan, and Germany should have alerted US regulators to the drug’s barbiturate-like properties. However, it was initially considered less problematic than barbiturates in nearly every region it entered.

The drug would go on to achieve notoriety in France, Italy, Sweden, Argentina, Norway, and Iceland due to its nonmedical use.

Germany

It launched in West Germany in 1960. The drug was initially marketed by Merck as “Revonal” and it was sold in 200 mg and 300 mg tablets.

In 1962, it launched in East Germany as “Dormutil.”

The substance was sold over-the-counter in both regions, unlike barbiturates. German observers said the extensive advertising of methaqualone and its reputation as “safe” helped it become popular.

Fatal overdoses associated with the drug were reported by 1962.

Between 1960 and 1963, 11% of the 611 overdose cases treated at Hamburg’s four medical centers involved methaqualone. Nearly all of the patients were in their 20s.

From 1963 to 1966, Dormutil in East Germany accounted for 22% of the 73 overdoses treated at Grietswald University Medical Center.

When other sedative-hypnotics were removed from the West German OTC market in 1962, methaqualone received a boost. Revonal became the top drug responsible for sedative-hypnotic overdoses.

Berlin’s Reanimation Center saw 300 sedative-hypnotic overdose cases in 1962. Of those, 23.4% came from Revonal alone or in combination.

Prescriptions were required for the drug beginning in 1963, at which point the number of overdoses reportedly declined significantly.

Japan

Eisai Company brought Hyminal to Japan in October 1960. It was freely available without a prescription.

By 1964, the World Health Organization Committee on Addiction Producing Drugs highlighted:

[The] epidemic-like outbreak of abuse of hypnotic drugs in a particular region. Methaqualone…is now reported to constitute four-fifths of the total amount of hypnotic drugs abused in the group studied.

Though Japan wasn’t named in the report, some have suggested it was the region under discussion.

Dr. Masaaki Kato reported that from April 1961 to December 1962, there were 1,942 youths arrested for delinquent activities who had “abused” methaqualone. Most were arrested in groups and they often took Hyminal together in coffee shops.

15-year-olds made up the largest portion of the “abusers.” Kato suggested this was because compulsory education ends at 15, at which point admission into prestigious high schools is very competitive and anxiety-producing, therefore increasing the desire for a sedative-hypnotic.

The Japanese government began to recognize some problems with the substance within a year. In November 1961, it began requiring drug containers to say, “Warning–habit forming.”

A survey of 411 drug users/addicts treated in Japanese hospitals found that from 1963 to 1966, 42.8% had “abused” methaqualone. That was a higher rate than for meprobamate (27.2%).

In June 1964, it was designated a “powerful drug,” limiting its availability to pharmacies. All containers now had to say “powerful” in red letters. No pharmacist, manufacturer, or importer could sell or give methaqualone to anyone unless they filled out a form with their name, the amount of the drug, the drug’s purpose, the date of transfer, and the name/address/occupation of the recipient.

The drug could no longer be sold to those under the age of 14 or to people considered unlikely to handle methaqualone with care.

These restrictions were strictly enforced.

UK

Boots Pure Drug Company introduced Melsedin in 150 mg tablets in 1959. Promotion of the drug was minimal, so sales of Melsedin didn’t peak until 1966, after which they gradually fell.

Between the drug’s introduction and 1966, just five instances of Melsedin abuse were reported, all of which involved habitual ethanol or barbiturate users.

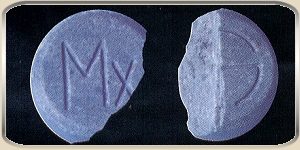

In 1965, demand for a nonbarbiturate “safe” sleeping drug was significant, especially after the failure of thalidomide. Roussel Laboratories met that demand with Mandrax, a new preparation combining methaqualone with a common dose of diphenhydramine. The preparation included 250 mg of methaqualone and 25 mg of diphenhydramine per pill.

There was a “vigorous” marketing campaign for Mandrax, which made it significantly more popular than Melsedin. Many British doctors, often due to statements from Roussel, thought it was superior to barbiturates, safer, and had a lower abuse potential.

Prescriptions jumped significantly, while the use of barbiturates fell. Mandrax prescriptions from family doctors in England and Wales went from 45,000 in 1965 to 2 million in 1971. Prescriptions for barbiturates fell from 17 million to 12 million.

In Q1 1966, 15% of the overdose cases in Sunderland, England involved Roussel’s product.

(Lawson, 1966) – 5% of patients admitted to the Poisoning Treatment Center at the Royal Infirmary (Edinburgh, Scotland) had taken an acute overdose of Mandrax. In some areas, that figure increased to 15% of overdoses at certain time points.

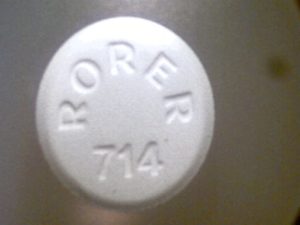

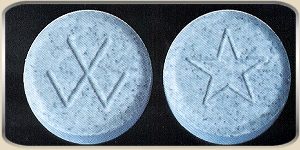

The substance was popularly known as “Mandies” or “Randy mandies.” Recreational users reported it offered a pleasant tingling sensation and euphoria. Because it could also lead to incoordination, another nickname was “wall bangers.”

By 1968, drug treatment clinic doctors in the UK reported a big rise in Mandrax use. A survey of heroin addicts at three London clinics in 1969 found 91% had used methaqualone at some time, while 51% took it daily. The primary reasons for use were to induce sleep and to provide pleasure.

Dr. Henry Matthew, director of the Regional Poisoning Treatment Centre, described the “widespread abuse of Mandrax for kicks” in 1971.

two Mandrax tablets, usually available on the black market for fivepence each, taken along with a glass of cider, produce what to teenagers is a very satisfactory high. – Matthew

Many young people got it from pubs and at parties, though they also relied on prescriptions. Thefts from retail and wholesale pharmacies were sometimes reported.

Its popularity further increased when heroin became more restricted in April 1968 and when injectable methamphetamine was withdrawn later in 1968.

The advent of the fashion of mainlining barbiturates seems to some extent to have reduced the abuse of Mandrax. . . . Mandrax seems to be still very popular, but because of the difficulty of dissolving the tablets, is usually taken orally. Addicts attending the treatment centres often urgently demand barbiturates or Mandrax. – Glatt, 1969

This kind of widespread use eventually led to actions from the UK government. It was placed in the Drugs Prevention of Misuse Act in 1970. This meant it became a criminal offense to import methaqualone except under Home Office license or to possess the drug without authority.

Manufacturers also responded by reducing the number of tablets per container and by adding new warnings about habituation/abuse.

Because of the abuse problem, we have undertaken no direct promotion of Mandrax for the past two years. In 1972, we withdrew the 1000 pill pack and are withdrawing the 100 pill pack on May 1. It will then be available in packets of 30 to reduce the danger of thefts from chemists and overdoses. We are in favour of tighter controls. Mandrax should be under lock and key in Chemists shops. – Roussel

The Misuse of Drugs Act of 1971 was updated in July 1973 to include methaqualone, further strengthening controls and increasing penalties. Certain regulatory measures, like requiring handwritten prescriptions, were implemented.

(Matthew, 1973) – In Edinburgh, the number of admissions for “attempted suicide” by Mandrax jumped from zero in 1965 to 10% of all adult self-poisonings in 1972.

After July 1973, the British Department of Health and Social Security reported a 60% decline in prescriptions.

Other

Overdoses from Mandrax became a somewhat notable issue in Australia. During an 18-month period ending September 30, 1969, the Royal Hobart Hospital in Tasmania reported Mandrax was responsible for 17/298 drug overdose admissions.

Statements from the global medical literature

During the early days of methaqualone in the US, regulators could have been aware of the drug’s nonmedical potential. Yet those concerns were basically ignored until the early 1970s.

In 1967, the British Medical Journal questioned “whether the alleged value of methaqualone outweighs its addictive potential.”

In 1969, the Medical Letter on Drugs and Therapeutics (a source of info for American clinicians) concluded the drug should be considered an addictive, physical dependency producing drug susceptible to abuse.

In 1970, the WHO Committee on Drug Dependence concluded the drug’s liability to abuse constituted a risk to public health and recommended it be placed under international control.

Physical dependence in the global literature

It’d take until the 1970s for methaqualone to truly be recognized as having physical dependence potential, yet it shouldn’t have taken that long.

(Madden, 1966) – Four cases that met 3/4 criteria for barbiturate-type dependence based on WHO criteria.

(Ewart, 1967) – A 47-year-old had withdrawal symptoms after abrupt cessation of methaqualone (60x 150 mg tablets per day). Delirium tremens was seen.

(Kato, 1969 – Japan) – Observed 176 methaqualone users. Found 16 had withdrawal symptoms of the delirium tremens type and 12 had convulsions.

Early 1960s

Before Quaaludes appeared in the US, methaqualone was sold in some combination products. It was marketed by the RJ Strasenburgh Company Division of Wallace and Tiernan.

Methaqualone wasn’t sold on its own, however. It was part of Biphetamine-T and Akalon-T, which combined it with amphetamine.

Biphetamine-T 12 1/2 included 40 mg of methaqualone with 6.25 mg amphetamine + 6.25 mg of dextroamphetamine. Biphetamine-T 20 had 40 mg of methaqualone with 10 mg each of amphetamine and dextroamphetamine.

Early 1960s

Potential side effects, such as paresthesia, became more well known. (Buckler, 1963) recounted two instances of paresthesia. The first was in 1961, when a physician reported transient paresthesia in the limbs of himself and his wife. The second was in 1963, when a patient under the care of Dr. McQuaker reported the symptoms.

At this time, paresthesia was considered a possible sign of significant toxicity. This view (later proven inaccurate) could have partly stemmed from the peripheral neuropathy issues that had been reported with thalidomide around the same time.

1960s to early 1970s in the US

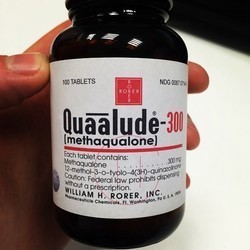

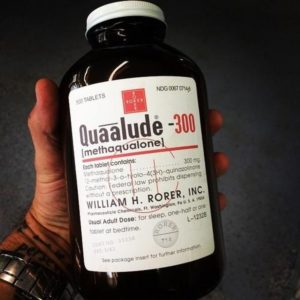

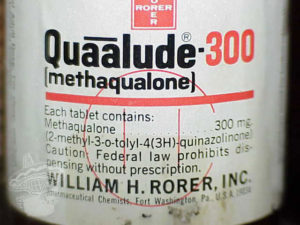

The FDA approved methaqualone on its own in 1965 and there were minimal controls in place regarding prescribing practices. William H. Rorer began selling it as Quaalude, which was advertised as a safe and non-addictive drug. It was primarily given for insomnia and anxiety.

Methaqualone, both in the US and elsewhere, was portrayed as safer than barbiturates, as having a low abuse potential, and as having nice hypnotic qualities (a rapid 10-30 min onset and a 6-8 hour duration.)

All the way into the 1970s, prescribers and users believed it was substantially safer than barbiturates.

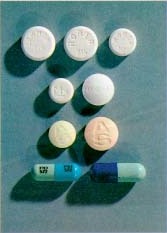

After Quaalude entered the market, competitors from Arnar-Stone (Sopor) and Parke Davis (Parest) appeared.

Nonmedical use was reported well before 1970, yet it was largely ignored. The Physician’s Desk Reference said the substance had rarely been associated with psychological or physical dependence, which also helped its reputation. Though that source also warned against giving it to people with a history of drug addiction.

Widespread prescribing was partly facilitated by a lack of restrictions. Prescribers were only required to prescribe the drug in an “ethical” way.

When reports tried to claim (albeit sometimes without adequate proof) that methaqualone wasn’t as safe as commonly believed, Rorer fought back. In a Letter to the Editor of the British Medical Journal on July 9, 1966, the company responded to another letter that claimed to show physical dependence. In reality, insufficient evidence of dependence (even though the concern was legitimate) was provided, so Rorer had some ground to stand on.

This is an unfortunate lapse, and one which, by misinformation, indicts without justification a relatively safe and effective sedative-hypnotic. – Gustav J. Martin, director of research, William H. Rorer

There were several large incidents of large amounts of methaqualone being stolen or diverted that were reported to the Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs. In one, a large manufacturer reported the theft of 600,000 methaqualone capsules, which were taken from bulk shipping drums during processing. It took 10 days for the manufacturer to know about the theft.

Another incident involved an arrested individual with 2,200 tablets in their possession claiming the drug had been diverted from a distributor.

Despite early reports of nonmedical use, the FDA in 1967 approved the marketing of a new 300 mg version of Quaalude, doubling the per-tablet dose.

Survey of drug treatment agencies in 8 states

- Prior to 1970: No reported cases of methaqualone abuse in the survey group.

- 1970: Small percentage (8.0%) of the 5,200 patients had abused methaqualone. Most users at this time were “hardcore users” (i.e. heroin addicts).

- 1971: Dramatic rise in methaqualone “abuse” and according to the paper author, a “silent epidemic had begun.”

- 1972: Increased further; half of the patients surveyed had abused methaqualone.

Use among young people

Methaqualone reportedly became a top drug in some high schools. Evidence in support of this comes from “Youth Consultant” programs in eight school districts in New York. Those programs were experimental drug abuse prevention and treatment initiatives.

All of the Youth Consultants reported the use of methaqualone in their distracts. Several had been aware of a dramatic rise in use/abuse among Junior and Senior high school students since Spring 1972.

The illicit selling price was reportedly $0.75 to $1 per pill.

This drug (methaqualone) is preferred to many of the standard barbiturates by those involved in drug abuse. Another alarming fact which was given to us by a number of youths is the fact that many parents whose children are involved in abuse of drugs knowingly tolerate the consumption of the drug (and even supply it!) because they do not consider Quaaludes and the others as dangerous in comparison with the more standard chemicals. – Jack Palmar, assistant director, Kinsman Hall (community for young drug users)

In 1970, the FDA required stricter labeling on ads and patient labeling. Yet the language still wasn’t harsh. Rorer now just claimed “psychological dependence occasionally occurs” and “physical dependence [has] rarely [been] reported.”

1970s in the US

Sales in the US were reported to be $3.4 million by 1970. An estimated 91 million units were prescribed in 1971, rising to 116.5 million in 1972. Quaalude alone earned Rorer $4.2 million in 1972. Sales had increased 360% since 1965 by 1972, making it the 6th best-selling sedative-hypnotic in the US.

Research at a clinic in Philadelphia and at the Haight-Ashbury Free Clinic in San Francisco documented a lot of methaqualone abuse and found the substance could produce physical dependence that was cross-tolerant with barbiturates.

When dependence appeared, it tended to be treated with pentobarbital tapering.

Methaqualone had initially showed up in the Haight-Ashbury district of San Francisco shortly after the “summer of love” in 1968, but people quickly moved on to heroin and barbiturates instead. However, around 1972 and 1973, methaqualone became more popular in the San Francisco Bay Area.

A short survey of patients at a San Francisco drug detox program in January 1973 found 15% reported moderate to heavy abuse of methaqualone in the past, 20% had tried it “a few times,” and 65% had never used it. The use of methaqualone in the area was fairly recent, with 57% of users saying they first took it in 1972. Only 8.5% had used it prior to 1971.

From January 1971 to May 1972, the BNDD said methaqualone was connected to 53 suicide deaths, 267 arrests, and 313 nonfatal overdoses.

The National Clearinghouse for Poison Control Centers reported 197 cases of poisoning from June 1971 to November 1972.

Info compiled by the Drug Abuse Warning Network (DAWN), a BNDD project, showed 1,440 instances of methaqualone abuse from September 1972 to January 1973. 675 involved self-administration for euphoria, 219 for “unhappiness,” 167 due to dependence, 90 for self-destruction, and 278 for unknown reasons.

The BNDD also documented “over a thousand cases” where opioid users combined it with methadone. And the agency claimed the drug was often used with alcohol, though it could also be used with heroin, barbiturates, and methadone.

(Pascarelli, 1973) – One eastern University saw an alleged 5,000 pills being sold illicitly per day.

In 1972, Hunter S. Thompson wrote about the drug’s alleged presence at the Republican and Democratic conventions:

During both conventions (Republican and Democratic), Flamingo Park was known as “Quaalude Alley” in deference to the brand ofdowners favored by most demonstrators. Quaalude is a mild sleeping pill, but-consumed in large quantities, along with wine, grass and adrenalin-it produces the same kind of stupid, mean-drunk effect as Seconal (Reds). The Quaalude effeet was so obvious in Flamingo Park that the “Last Patrol” caravan of Vietnam Vets . . . refused to even set up camp with the other demonstrators . . . . The last thing they needed was a public alliance with a mob of stoned street crazies and screaming teenyboppers.

Rorer updated Quaalude’s package insert in 1972 to include:

Coma has occurred with acute overdoses averaging 2.4 gm. Death has occurred following ingestion of 8 gm. In other cases, patients have survived ingestion of up to 22 gm. Most fatal cases have followed ingestion of overdoses accompanied by alcohol.

(Gerald, 1973) – Survey of methaqualone users in Ohio

- 66 participants from April to May 1972

- Occupation

- 52% were students, 27% were employed, and 11% were unemployed or seeking employment.

- Results

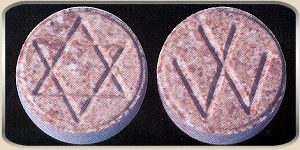

- Mainly used 300 mg tablets marketed as Sopor (from Arnar-Stone) and Quaalude (Rorer)

- Frequency

- Several times daily – 3.3%

- Daily – 6.6%

- Weekends only – 20%

- Weekly – 31%

- Monthly or a few times – 39%

- Though, there’s reason to think the “weekly” users actually used multiple times per week.

- Duration of use

- Average: 1 year

- Under 6 months – 29%

- 6 to 12 months – 21%

- 1 year – 30%

- Over 2 years – 20%

- All regular use involved oral administration; some experimentation with smoking, intranasal, or injecting.

- Manner of use

- Typically said to be a “social” activity — People will use with at least one other and sometimes quite a few people.

- Primary reasons for trying

- Curiosity, recommendation by friend, “desire to get high,” “the desire to escape from my problems,” and “to achieve relaxation.”

- Personal friends introduced people 83% of the time.

- Drug of choice

- Just 15% considered methaqualone their DOC

- It was among the top three in 51%

- 69% said cannabis was their DOC

- Combinations are common

- 94% smoked cannabis at least half of the time they were on methaqualone

- Dose

- Average: 530 mg

- 300 mg – 25%

- 400 mg to 500 mg – 28%

- 600 to 800 mg – 31%

- 900 to 1500 mg – 15%

- Average: 530 mg

- Timeline

- Onset of 30 minutes (15 to 120 minutes)

- Max effects after 60 min (30 – 240 minutes)

- Duration of 4 hours (1 to 8 hours)

- Effects

- While paresthesia is minimal at medical doses, 75% of respondents reporting “tingling of the body” at least 50-100% of the time.

- During the first 2 hours of the effects, subjects most often reported listening to music, conversing with friends, sleeping, or engaging in sexual intercourse.

- Negatives in first 2 hours

- 54% had muscle weakness, 54% had weakness of the ankles or knees, 43% had dizziness, and 32% had disorientation towards personal identity or location.

- 5 – 25% reported: nausea, diarrhea, tremors, chills, and headache.

- 10% felt they were “losing their mind.”

- Negatives from 8 – 24 hours

- 26% headache, 19% hangover, 17% disorientation, 12% dizziness, 11% felt they were “losing their mind.”

- One respondent attempted suicide with 6,900 mg at one point.

- Severe adverse

- 5% knew of three persons each who became very ill after taking large doses

- 22% indicated they knew of 3 – 5 people who became very ill from methaqualone mixed with alcohol

- Withdrawal

- Several days after abruptly stopping: nervousness, irritability, and anxiety (5-6), depression (5), abdominal pain (3), auditory and visual hallucinations (2), and tremor (1)

Media and literature coverage

The media began heavily covering methaqualone, typically highlighting its sheer popularity, in the early 1970s. Some articles also exposed the drug’s nonmedical, dependence-producing, and toxic potential.

Here are some examples of pieces from the time period:

The Washington Post in 1972 (by Daniel Zwerdling)

Declared methaqualone “the ‘safe’ drug that isn’t very.”

The double A in Quaaludes has stood not only for growing profits…but for addiction and abuse as well.

An addiction specialist in NYC warned the drug “was all over the place and getting even bigger.”

Dr. Lois Chatham, chief of the Narcotic Addiction Rehabilitation Branch of the National Institutes of Health, said:

There’s no doubt that [methaqualone has] suddenly become a rage,

Summed up:

The methaqualone boom should make an interesting case study in future medical textbooks [about] how skillful public relations and advertising created a best-seller and helped cause a medical crisis in the process.

The Washington Post in 1973

Said the drug had become popular in part because federal agencies endorsed its “good drug” image.

The Michigan Daily in 1972 – “Quaalude withdrawal is dangerous”

Dr. Philip Margolis of University Hospital said: “Our own experience with Quaalude shows that it is probably addicting.”

Dr. Richard Kunnes, Washtenaw County Community Mental Health Center:

It’s clear we’re only seeing the tip of the iceberg in terms of the number of people addicted…Addiction within four to six weeks could occur very easily.

Kunnes estimated there were “hundreds of people” addicted to the drug just in the county. And he said it could be more dangerous than heroin due to “potentially fatal” withdrawal.

Time in 1973

[Methaqualone is] so fashionable among some drug cultures that bowls of it have replaced peanuts as a cocktail-party staple.

The New Republic

Felt federal agencies played an important role in making the drug popular.

Drug firms have been building a safe image for methaqualone in their advertising, much of it in medical publications. These ads have led many people to believe the drug is a nonaddictive “downer” when in fact it is every bit as dangerous as barbiturates.

The ready availability of methaqualone on the streets and in the schools has little to do with clandestine laboratories: it stems from the absence of federal controls on prescriptions, production and security.

“Sopors Are a Bummer” (1973)

The article discussed how as early as 1969, Sopors were being shipped by the thousands from Colombus, Ohio to the University of Cincinnati. It was claimed to be as popular as barbiturates by the early 1970s.

Multiple references from (Wesson, 1972)

The drug was reportedly called “heroin for lovers” by some groups.

A San Francisco Chronicle piece in November 1972 called it the “hottest drug on the streets.”

On March 29, 1973, the drug appeared on the cover of Rolling Stone. The story was called “Unconsciousness Expansion: The Sopor Story.”

Quotes from users:

It’s utterly fantastic. Quaalude made me feel friendly, open and receptive. In fact, it made me feel permanently receptive. I got into things I’d never gotten into before and they’re still with me.

Other downs bring me too down. I just fall out, so I have to fight them and by the time I stop fighting, I’m not high any more. Quaalude calms me down and makes me mellow and loose. I want to dance, talk, dance, cook; I can even drive on it. And I can make love on it very nicely. But I don’t lose control at all and there’s no hangover; I’m always alert the next morning.

Quotes from Dr. George Gay, director of clinical activities at the Haight-Ashbury Medical Clinic. He was also a special consultant with the FDA who wanted methaqualone to be rescheduled.

Qualitatively and quantitatively there is no discernible difference between Quaalude or Sopor and reds, the barbiturates. Quaalude has all the bad qualities of barbs. It’s a respiratory depressant, and when it’s taken in combination with other downs or alcohol there is an additive effect. It can totally suppress breathing.

And although the drug companies and the Physicians’ Desk Reference don’t acknowledge this, it is addicting. Ten Quaaludes a day for a month is enough to give you a physical habit, such that if you stop flat, cold turkey, you will exhibit the prodrome to convulsions, just like a barbiturate addict: sweating, disturbed sleep and nightmares, white-knuckled tension. Methaqualone has only been popular for a relatively short time, and I have no doubt that soon we’ll be seeing addicts with heavy enough habits that they actually will go into convulsions.

We had Quaalude here in the Haight briefly in ’68,’…Then it faded, probably because of the smack epidemic. In ’68 and ’69 there was a lot of up-down scene, following the big speed era. The bikers moved into the Street and brought their own street pharmacology for easing the comedown from speed. They’d take barbs or smack after a couple of days’ speed run. Then in ’71 the Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs started scheduling drugs, and barbs became harder to get—though of course there are still twice as many barbs manufactured as are sold by prescription.

Then Quaalude showed up in Florida and Washington, D.C. It started being noticeable here in ’71 and has increased greatly in the last year. In fact, it’s everywhere. In Illinois, say, it’s a visible problem in the black community. In Houston it’s made inroads among young whites.

There is a strong regionalism to the problem. Rorer, which makes Quaalude, is located right outside Philadelphia, and Philadelphia is saturated with Quaalude. Wallace, in New Jersey, makes Optimil; New Jersey has an Optimil problem. Likewise Parest, made by Parke, Davis in Detroit. Sopor, made by Arnar-Stone in Mt. Prospect, Illinois, is big in St. Louis and Chicago, all over the Midwest.

The Physicians’ Desk Reference says nothing to warn the doctor about methaqualone. If you look up under Parest or whatever, you’ll only find something like, ‘contraindicated for persons with liver disease, pregnant women or any woman who may become pregnant, people under 14.’ What the hell does that mean? It means it’s an experimental drug. I wouldn’t prescribe a pregnant woman aspirin, for that matter.

It may say, ‘pending longer term clinical experience, should not be used continuously for periods exceeding four weeks,’ or three months, depending on the manufacturer. It recommends against prescribing to an ‘addictive personality,’ but without exception it says addictiveness is ‘not demonstrated’ or ‘rarely reported.’ The poor overworked doc gets big boxes of samples from the drug company, looks up in the PDR and nothing there says it’s addictive, it looks clean, and so he starts passing them out. He doesn’t know he’s doing anything harmful.

Of course by now there are scrip doctors who are signing prescriptions to huge amounts of the drug. We know of a doctor who signed a scrip for 300 pills one day, then turned around and prescribed 300 more to the same patient the next day. Fully a third of the people we see here at the Clinic who’ve done Quaalude have gotten it from a doctor. It sells in the street about 30¢, but it wholesales for $5.60 per hundred, five and a half cents apiece. I suspect there is some kickback going on between the pharmacist and the scrip doc.

And people are fixing it like smack now, too. It’s much worse to shoot than smack because it’s so alkaline. It’s like shooting barbs; it causes cellulitis and abscesses.

But what a drug to take. It has all the possible disadvantages a drug can have. It’s a garbage drug, a real drug of abuse.

Editorial in Clinical Toxicology in 1973

Described the drug’s use as a “craze” and said it had become “the most desired drug for non-medical use on the street and college markets.”

Florida Medical Association Journal

Called it the “most recent fad of drug abuse.”

Journal of Mississippi Medical Association in 1973

Methaqualone is one of the most desired, if not the most desired, drug for nonmedical use on the street today.

On the street they are known as Quales . . . Soaps . . . Ludes, Love Pills . . . the hottest drug going. After all, they aren’t addicting, they take away all your troubles, they give you a great body feel, and unlike heroin, which puts you out of the scene entirely, they are great for lovin’. If you don’t believe it, ask anyone in the drug scene. The best part of all is that they are easy to come by legally. All you need is a script from your family physician and you can get it legally . . . refill it as often as you want without any problem. After all, it isn’t even mentioned under the Drug Abuse Control Act of 1970. What more could any ‘drugger’ ask for?

US military forces in Europe

Fairly widespread use of the drug by US military personnel stationed in Europe was seen during the early 1970s.

It was often used alongside hashish or alcohol. The drug was rarely officially encountered pre-1972, but that could be due to a lack of drug testing. Though more than 50 products in Germany contained methaqualone, Mandrax was responsible for 95% of the use by US soldiers in the region. Often they’d obtain the drug using forged prescriptions.

In 1972, US Army hospitals in Germany had 10 admissions per month for Mandrax-related problems, mainly overdoses. It accounted for 5% of all drug abuse-related admissions.

(Tennant, 1973) – Reported on methaqualone complications in 67 troops in Europe.

There was a rise in admissions during 1973, reaching 59 per month in Germany on average. A total of 713 were reported during that year. 289 came just from Mandrax, 40 involved a combination with alcohol, and 384 involved Mandrax with other drugs (e.g. hashish) and sometimes alcohol.

A similar level of use in Germany was seen in 1974, though the average was 44 admissions per month.

Methaqualone accounted for 10-15% of total drug abuse hospital admissions from 1973 to 1974.

Physical dependency

(Richardson) – 12 cases of methaqualone dependence requiring detox seen at Frankfurt Army Hospital. All were initially tolerant to 200 mg pentobarbital. They had reportedly used 7 to 25 Mandrax pills daily.

Outpatient rehab admissions

During 1973, 841 people were clinically confirmed as Mandrax abusers, including both inpatients and outpatients.

During 1974, there were 1,126 cases.

Mortality

Prior to 1973, no fatalities were linked to methaqualone.

There were 17 in 1973 and 18 in 1974.

This covers all of the cases with a positive test for methaqualone, but other drugs were often involved and the deaths sometimes came from trauma/accident.

Random survey of US Army members

- September and October 1973: 7,545 urine samples

- Positive rate of 2.9% and 3.9%, respectively.

- June and July 1974: 15,242 urine samples

- 1.34% positive rate

- Compared to 0.11% for barbiturates and 0.14% for amphetamines. Though opioids were higher at 1.85%

- None had used methaqualone prior to arriving in Europe.

1970s – Pushing for a crackdown

In 1972, a Washington DC drug abuse task force officially petitioned the Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs to place the substance in Schedule 2. It took a year for the BNDD to consider this move, which led Senator Birch Bayh to put pressure on the agency by proposing a special law that’d bypass the agency.

Bayh held hearings on the matter, bringing in many “experts” to discuss methaqualone’s use and properties.

A University of Michigan psychiatrist testified at Bayh’s hearings, describing his experience with methaqualone users who appeared at his clinic:

[The users] uniformly stated that they took Quaalude in place of or in avoidance of addicting drugs. As such, these people did not seem to have many of the psychological symptoms associated with drug abusers and addicts, but rather appeared to be drug users and experimenters who unknowingly got hooked.

During the hearings, FDA chief Gardner said there was “nothing in the FDA files or the medical literature to alert us to problems” of abuse or addiction. However, he admitted there was “widespread nonmedical consumption by individuals who are unaware of or not concerned with the hazards of the drug.”

The Second Report of the National Commission on Marihuana and Drug Abuse (1973) said “the risk potential of methaqualone is roughly equivalent to that of the short-acting barbiturates.”

That report recommended Schedule 2 status:

Since, unlike the barbiturates, methaqualone does not have large-scale medical uses and does present a significant problem of misuse, it should be placed in Schedule II along with the amphetamines.

A paper from Ostrenga in 1973 clearly pointed out the harm potential of the drug, going against some common views.

Contrary to medical opinion and claims by drug companies, prolonged use of methaqualone does cause physical tolerance and psychological dependency similar to that of barbiturate addiction.

Shocking as it may be, this drug in reality is as dangerous and addictive as barbiturates. It is ironic that a legal and allegedly “safe as aspirin” drug is quickly becoming one of today’s major drug-abuse problems. The notoriety created by the methaqualone craze has now forced the BNDD and the FDA to reconsider their original ratings of the drug. The BNDD is considering moving methaqualone to Schedule 2 under the Drug Abuse Control Act of 1970 – on par with methadone, morphine, amphetamines and barbiturates.

Rorer challenged the call for Schedule 2 status. It argued there should be new controls on the drug, but that Schedule 3, which came with less oversight and no domestic production restriction, would be sufficient. Rorer also said there was little evidence supporting its addictiveness.

Ultimately, the BNDD’s interest in Schedule 2 status prevailed. The drug was placed in Schedule 2 in 1973.

Mid 1970s

Just in the first year of its Schedule 2 status, prescriptions reportedly fell by half. Domestic production quotas also aggressively dropped as the years went on, falling from 25 million in the 1970s to 12.5 million by 1980.

Despite it being Schedule 2, supply and demand failed to disappear. Prescribing continued and an illicit market was available. Some markets were entirely criminal, driven by fake companies, stolen supplies, and forged prescriptions.

A lot of the market involved drug diversion or the use of “scrip doctors” at “stress clinics.” At those clinics, licensed and DEA registered physicians prescribed methaqualone for a fee to anyone complaining of stress. The clinics effectively only provided methaqualone.

Late 1970s and early 1980s

Rorer sold its rights to Quaalude to Lemmon Pharmaceuticals in 1978. A letter to stockholders from Rorer chairman John Eckman explained this decision:

Quaalude accounted for less than 2 percent of our sales but created 98 percent of our headaches…Continued publicity about the abuse of this product was hurting the reputation of the company.

The DEA’s Automation of Reports and Consolidated Orders System (ARCOS) found a 50% decline in retail drugstore and hospital pharmacy purchases of methaqualone from 1976 to 1979. DAWN indicated 12% of methaqualone users in hospital EDs reported “legal prescriptions” as their source in 1979. That was down from 28% in 1976, indicating a shift to illicit supplies. And the percentage reporting “street buys” went from 12% in 1976 to 43% in 1979.

After experiencing a decline in use in the mid-1970s, there was a resurgence in popularity around 1978. For example, in George, the occurrence of methaqualone in biological samples during DUI cases increased 451% from 1978 to 1979.

Federal officials reported 117 deaths from illicit methaqualone in 1980, up from 87 in 1979.

The DEA found 75% of methaqualone samples submitted for examination in July 1980 had been clandestinely produced.

(Gonzalez, 1981) – Detailed piece on JAMA

Gene Haislip, director of the Office of Compliance and Regulatory Affairs within the DEA.

Says methaqualone is the leading drug of abuse next to cannabis. Many people are using illicit, not diverted, products. Those can contain anywhere from 25 to 500 mg of the drug or entirely different substances.

The people making these up don’t care what they’re doing.

Haislip advised physicians to keep this issue in mind:

Consider that the actual drug may be something else, or may be methaqualone in another dose…In the case of an overdose complaint, inquire into the source of the drug.

100+ tons of methaqualone from around the world was reportedly smuggled into the US in 1980. The DEA actually seized 15 tons of illicit methaqualone in 1980. That’s compared to the legal production and distribution of just 4 tons of domestic methaqualone.

Speaking on the supply chain, Haislip said the illicit supply tends to come from eastern and western Europe. West Germany, Austria, and Hungary are major sources.

Bulk powder is made legally by pharmaceutical companies in some regions. It’s then purchased through brokers who may knowingly handle the illicit orders and even mislabel shipments.