Cathinone is a naturally occurring amphetamine found in khat (Catha edulis). It’s rarely used outside of khat, where it works in combination with other drugs to provide fairly typical stimulant effects.

Occasionally it’s been sold on its own, but cathinone itself is a rare product. Khat, however, is used by millions of people every day.

The drug offers amphetamine-like effects, including stimulation, mood lift, and increased cardiovascular activity. Khat has long been used to facilitate social interaction, to provide stimulation, and to decrease hunger.

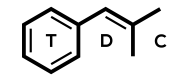

Cathinone serves as the base structure for a large class of drugs, the substituted cathinones.

Cathinone = benzoylethanamine; β-keto-amphetamine; beta-keto-amphetamine; (S)-(-)-Cathinone

PubChem: 62258

Molecular formula: C9H11NO

Molecular weight: 149.193 g/mol

IUPAC: (2S)-2-amino-1-phenylpropan-1-one

Contents

Dose

Oral (tentative)

Common: 30 – 60 mg

We don’t have good dosing information for cathinone itself.

Khat is typically chewed during 3 to 5-hour sessions and an estimated 100 – 300 grams is used per session. That’d come out to 30 to 100 mg of cathinone per use, but the amount of cathinone exposure could vary significantly.

The plant is most often chewed or made into a tea. Occasionally it’s been smoked.

Khat users tend to prefer fresh leaves and they chew intermittently to enhance the absorption.

Timeline

Oral

Total: 2 – 4 hours

Onset: 00:15 – 01:00

Typically people use khat over a period of hours, with the effects peaking around 90 to 210 minutes after the session begins.

In pharmacokinetic studies, cathinone is almost undetectable at both T+00:30 and T+07:30.

Experience Reports

Effects

Positives

- Euphoria

- Stimulation

- Mood lift

- Increased alertness

- Increased talkativeness

- Increased motivation

Negatives

- Anxiety

- Insomnia

- Dry mouth

- Hyperthermia

- Aggressiveness

- Restlessness

- Tachycardia

- Hypertension

- Vasoconstriction

The effects described on this page primarily come from reports of khat’s activity. Even though there are other active drugs in khat, cathinone is the primary substance. It’s safe to treat most of the acute effects of khat as coming from cathinone.

Khat typically produces a state of alertness, often accompanied by mood lift. It can facilitate conversation and make people more interested in discussions. If too much is used, it can impair concentration.

By the end of a khat session, people frequently report a depressive mood, irritability, appetite loss, and insomnia. These comedown effects are similar to what’s seen with other stimulants.

Cathinone is used similarly to amphetamine, though there are some khat-specific cultural uses. Khat sessions (typically male-only) are a popular time to discuss important societal matters and it’s sometimes used to assist prayer.

Outside of those settings, the substance is used as a study/work aid and to remain awake during shift work. Even though the method of exposure may be different (plant vs. isolated drug), khat use often appears reminiscent of the way someone would take amphetamine or methylphenidate.

Muslims are some of the most avid users of khat, yet there are ongoing debates in some countries over the permissibility of the drug. Some argue it’s prohibited under Islamic law. Others claim it’s endorsed as a prayer aid and has been used since the time of Muhammad.

Negatives

Anxiety and paranoia are the primary psychological negatives. They’re more common with overdoses.

On the physical side, the most prominent negatives are found with the cardiovascular system. It can lead to tachycardia, hypertension, palpitations, and vasoconstriction. Again, overdoses are the most concerning. Though even typical doses can increase heart rate and blood pressure.

Some of the less-common negatives include migraine headaches, cerebral hemorrhage, myocardial insufficiency, stroke, myocardial infarction, and pulmonary edema.

These negatives have sometimes been associated with fatalities and medical emergencies arising from khat or cathinone use.

Long-term

It appears there is a lot of fearmongering around khat both from foreigners and from locals in Arabia and Africa. As such, it’s difficult to figure out what the true long-term negatives are.

Among the issues that have been alleged are anorexia, constipation (likely more with khat than cathinone), and reproductive problems. The alleged reproductive problems with heavy chronic use include spermatorrhea and impotence, along with delayed ejaculation in males.

Traditional medicine

Khat has a long history of use in some African and Arabian countries, yet it’s not a popular traditional medicine. But there are exceptions.

In Kenya, the Meru tribe has used it for erectile dysfunction, malaria, influenza, vomiting, and headache.

In Ethiopia, a tea is traditionally prepared to reduce mouth swelling and to lower blood pressure.

In Yemen, some users consider it helpful for headaches, colds, body pains, fevers, arthritis, and depression.

In the Tanganyika region (now known as Tanzania), the leaves and roots are used for influenza, and the roots are used for stomachache.

In Arabia, it used to be promoted as a protection against the Bubonic plague.

Chemistry & Pharmacology

Chemistry (and some botany)

Khat is a hardy plant capable of growing in various climates and soils, including during droughts and in locations where other crops fail.

It contains dozens of alkaloids and other substances, many of which haven’t been fully explored.

Fresh young khat leaves are said to be more potent, which could be due to a higher cathinone concentration. It appears plant maturity reduces the cathinone concentration, yielding more cathine. Drying, though long believed to remove cathinone, doesn’t actually ruin the plant’s potency.

Khat contains other substances, but they’re not vital for the psychoactive properties. Cathine, for example, could play a role in peripheral activity and the tannins could contribute to its safety profile. But much of the acute central and peripheral effects can be attached to cathinone.

7 – 14% of khat’s mass comes from alkaloids, terpenoids, flavonoids, sterols, glycosides, and tannins.

The form of cathinone found in nature is the S-isomer, which also happens to be more potent as a CNS stimulant than R-Cathinone.

Cathinone is also known as b-keto-amphetamine. It’s a simple substituted amphetamine.

Concentration

Report 1

- 100 grams of fresh Khat leaves:

- 36 to 114 mg of cathinone, 83 to 120 mg of cathine, and 8 to 47 mg of norephedrine.

Report 2

- 100 grams of fresh Khat leaves (Addis Ababa region of Ethiopia)

- 35 mg of cathinone, 120 mg of cathine

Report 3 (Toennes)

- 100 grams of khat leaves confiscated at Frankfurt airport

- 114 mg of cathinone, 83 mg of cathine, and 44 mg of norephedrine.

Report 4 (Widler)

- 100 grams of fresh leaves at Geneva Airport

- 102 mg cathinone, 86 mg cathine, and 47 mg norephedrine.

Report 5 (Motarreb)

- 100 mg of fresh leaves

- 78 to 343 mg cathinone

Pharmacology

Cathinone basically functions like amphetamine. It induces the release of dopamine and norepinephrine, resulting in the activation of central and peripheral catecholaminergic pathways.

Dopamine is the primary mediator of the psychoactive effects, but norepinephrine also plays a role and contributes to the peripheral activity.

By increasing the release of DA/NE and inhibiting their reuptake, the functional concentrations of both increase.

Cathinone can reduce the average and maximum urinary flow rates, likely from a1-adrenergic stimulation.

Serotonin

Cathinone has been shown to boost serotonin levels as well. This isn’t likely to contribute in a notable way to the effects in humans.

(Kalix, 1984) – Boosted labeled serotonin in rat striatal tissue at 1/3 the potency of amphetamine.

(Glennon, 1982) – Four times greater affinity than amphetamine for certain peripheral serotonin receptors.

(Wagner, 1982) – Repeated cathinone doses didn’t alter regional brain levels of serotonin.

(Fleckenstein, 1999) – High doses of cathinone administered to striatal synaptosomes from rats can result in decreased SERT function.

Studies have also found it can produce serotonin and 5-HIAA depletion, supporting the potential for serotonergic effects. And it’s been shown to boost 5-HT in nucleus accumbens and 5-HIAA in the prefrontal cortex.

None of the central serotonin activity is substantial compared to what’s seen for DA and NE. Cathinone is primarily a catecholaminergic drug.

MAO

It seems to exhibit MAOI properties in vivo. The inhibition level isn’t incredibly low, but it’s still pretty low and might not contribute to effects in humans.

While amphetamine has a Ki of 7.9 mM, cathinone’s is only 0.05 mM.

(Osorio-Olivares, 2004) – It inhibits MAO-B more than MAO-A.

Antagonist studies

Antagonist studies have supported the role of dopamine and norepinephrine in the activity of cathinone.

(Calcagnetti, 1992) – Psychostimulant activity blocked by DA release inhibitors, CGS 10746B and isradipine.

(Valterio, 1982) – Haloperidol, spiroperidol, and pimozide all blocked the locomotor response to cathinone, supporting a dopaminergic role.

(Kalix, 1981) – Cocaine and other DA reuptake inhibitors blocked the activity of cathinone.

(Hassan, 2005)

- 63 humans given khat to chew for 3 hours on 3 separate occasions.

- Either given placebo, indoramin 25 mg, or atenolol 50 mg before their sessions.

- Results

- Atenolol-treated khat group showed significantly lower SBP and HR values at 1, 2, and 3 hours compared to khat chewers given placebo or indoramin.

- Their cardiovascular values became similar to those not receiving khat.

- BP and HR weren’t altered when only atenolol was given without khat

- Atenolol-treated khat group showed significantly lower SBP and HR values at 1, 2, and 3 hours compared to khat chewers given placebo or indoramin.

- Interpretation

- Khat’s effect on SBP and heart rate is blocked by atenolol, but no indoramin, supporting an important role of beta-1 adrenergic receptors.

Khat is more than cathinone

Not every effect arising from khat comes from cathinone. Some of the safety concerns (e.g. oral cancer and other oral health issues) come from khat itself and even on the neurochemical side, khat contains additional active drugs.

(Banjaw, 2005)

- Postmortem neurotransmitter analysis 5 days after 9 consecutive days of S-cathinone, d-amphetamine, or khat extract in rats

- Only khat extract rats had reduced levels of dopamine, DOPAC, and HVA in the anterior caudate-putamen.

(Banjaw, 2006)

- Compared to cathinone, rats given khat extract had higher elevation of dopamine in the nucleus accumbens.

- Both showed similar depletion of serotonin and 5-HIAA in the anterior and posterior striatum.

(Houghton, 2011)

- Cathedulin fractions from khat were shown to increase release of dopamine from striatal tissues.

- There was also binding to D1 and D2 receptors.

Studies (other)

(Knoll, 1979) – 1 mg/kg cathinone in anesthetized rats or cats led to a substantial rise in blood pressure.

(Yanagita, 1979) – Confirmed cathinone’s BP increasing effect. It had a similar potency to amphetamine in vitro using isolated guinea pig heart.

(Knoll, 1979) – Looked at the impact on other organs with significant sympathetic innervation. Found constrictions of the rabbit ear artery induced by low frequency stimulation could be potentiated by cathinone with a potency akin to amphetamine.

(Schuster, 1979) – Mydriasis regularly seen in monkeys during behavioral experiments.

(Knoll, 1979) – Examined the flexor reflex of the hind limb of rats. Cathinone was as potent at generating a response as amphetamine, supporting its role as a central noradrenergic drug.

(Kalix, 1980) – Causes hyperthermia in rabbits.

(Yanagita, 1979) – Racemic cathinone led to pronounced restlessness in monkeys. Similar potency to d-Amphetamine for producing hypermotility.

(Zelger, 1980) – Looked at several behaviors in rats given racemic cathinone (20 mg/kg). Overall effect was similar to amphetamine, but not to apomorphine (DA receptor agonist), supporting a presynaptic role of the drug.

(Rosecrans, 1979) – Mice given 8 mg/kg cathinone. It had little impact on brain norepinephrine turnover, but significantly increased dopamine. Lower potency than amphetamine.

(Zelger, 1981) – In vitro using rat striatal slices. Racemic cathinone inhibited the accumulation of labeled dopamine in the tissue, supporting DA release/repuptake inhibition.

(Kalix, 1980) – Examining impact of cathinone on radioactivity efflux using isolated rabbit caudate nucleus prelabeled with dopamine. 4 uM of cathinone led to a rapid and reversible increase in radioactivity efflux. Amplitude of the effect was ~60% of that produced by the same concentration of a-Amphetamine.

(Zelger, 1981) – Rat striatal slices prelabeled with dopamine. 5 uM racemic cathinone had about 2/3 the efficacy of d-amphetamine for efflux of labeled dopamine. At 50 uM, the two were almost equipotent.

(Kalix, 1983) – Compared the potency of cathinone with cathine for release induction. Compared to cathinone, 8x more cathine was needed for the same effect.

(Kalix, 1983) – Confirmed, using labeled norepinephrine, that cathinone also induced the release of norepinephrine in rabbit atrium tissue. This supports the existence of norepinephrine release playing a role in the peripheral stimulation.

(Kalix, 1983) – Using rabbit atrium. Cathinone enhanced release at just 0.12 uM. Showed it’s more potent at peripheral noradrenergic nerve endings vs. at central dopamine storage sites. Cathine was found to have a releasing potency peripherally that’s equivalent to cathinone.

(Gugelmann, 1985) – Differences between the enantiomers

- Rats given S- and R-cathinone IP

- Studying locomotor activity

- At 1 and 3 mg/kg, locomotor activity with d-amphetamine was significantly higher than with cathinone, but at 6 mg/kg S-cathinone led to more activity.

- At 3 and 6 mg/kg, S-cathinone activity was significantly greater than R-cathinone.

- Maximally effective dose for R-cathinone was 15-18 mg/kg, around 2 to 3-fold higher than for S-cathinone.

- Interpretation

- The naturally occurring S-cathinone is only slightly less potent than dextroamphetamine as a CNS stimulant.

- And the S-cathinone isomer is significantly more potent than the R-isomer.

(Kalix, 1986) – Studying releasing effect at central and peripheral catecholaminergic sites. Samples of rat nucleus accumbens and striatum. And peripheral samples from rat vas deferens or atrium. S- and R-cathinone led to equipotent release at noradrenergic nerve endings peripherally, but central dopaminergic synapses saw a 3x greater potency from S-cathinone. Results also showed both isomers are considerably more potent at peripheral norepinephrine release vs. central dopamine release.

(Schechter, 1989) – Caffeine and nikethamide potentiate cathinone in rats

- Rats trained to discriminate 0.8 mg/kg S-cathinone from vehicle

- Then tested for discrimination with 0.2 mg/kg and 0.5 mg/kg

- Both led to partial response rates.

- When caffeine or nikethamide were added, the cathinone response was much higher, indicating potentiation of similar activity.

(Jones, 2014) – Found to raise temperature, locomotor activity, and striatal C-fos expression in hamsters

- 12 hamsters

- Given S-cathinone at 0, 2, or 5 mg/kg IP

- Results

- Temp and activity

- Dose-dependent rise in body temperature

- Statistically significant rise within 10 min from 5 mg/kg and within 20 min from 2 mg/kg

- Dose-dependent rise in activity

- Significant increase persisting for 60 min after a 5 mg/kg dose and for 30 min with 2 mg/kg

- Dose-dependent rise in body temperature

- Behavior

- Decreased inactivity and led to a rise in locomotor activity

- No other behavior affected at 2 mg/kg

- At 5 mg/kg, there was a rise in rearing, locomotor activity, twitches, and spinning.

- Decreased inactivity and led to a rise in locomotor activity

- c-Fos

- 5 mg/kg produced a rise in c-fos expression in the striatum

- And there was a significant rise in c-fos-ir cell nuclei in the SCN as well, but not other hypothalamic regions

- Temp and activity

- Interpretation

- The marked rise in c-fos-ir in the striatum could be linked to central dopaminergic activity and it fits with what’s seen with other stimulants.

- SCN c-fos expression increase could come from high dopaminergic innervation and the presence of D1 receptors in that region in hamsters.

Endocrine

(Nencini, 1984) – Increased ACTH levels in humans.

(Nyongesa, 2008) – Increased serum cortisol in rabbits.

(Mohammed, 2011) – Decrease in serum cortisol in rats given 5 mg/kg cathinone.

(Nyongesa, 2013)

- 14 monkeys

- Groups

- 2 in control

- Others received either: 0.8, 1.6, 3.2, or 6.4 mg/kg of cathinone

- Cathinone was administered orally 3x per week for 4 months.

- Results

- Dose-dependent decline in cortisol levels over the 4 month treatment period

- Levels during the treatment phase were generally lower than those during the 4 week pretreatment phase.

- Higher cathinone doses induced decrease in overall prolactin concentrations.

- There was no significant effect at 0.8 mg/kg

- Strong positive correlation between cortisol and prolactin during the treatment phase, indicating a similar mode of action.

- Dose-dependent decline in cortisol levels over the 4 month treatment period

- Interpretation

- Cathinone causes a dose and time-dependent decline in serum cortisol and prolactin.

- Limitations

- Animals had their blood sampled under ketamine anesthesia, which had an unknown impact on the observed concentrations.

Pharmacokinetics

Tmax: 72 minutes (reports indicate it’s 1 to 3.5 hours)

Half-life: Reported to be ~4 hours (range of 90 to 260 minutes)

Metabolism

Cathinone undergoes significant metabolism, including keto reduction to norephedrine and cathine. Norephedrine may be the primary metabolite.

Only a small amount is excreted unchanged in urine. One report found the cathinone recovery in urine was just 3.3%, with significantly greater recovery of metabolites.

Studies

(Brenneisen, 1986)

- 3 human volunteers received 24 mg of R-cathinone, S-cathinone, or racemic cathinone

- Primary metabolites were aminoalcohols, namely cathine and norephedrine.

- 21-50% of cathinone was recovered in urine as aminoalcohols, while 0.6 – 3.3% was the unchanged drug.

(Halket, 1995)

- 5 adults; khat-naive

- Given ~60 grams of leaves from Ethiopia to chew for 1 hour; no swallowing of the residue.

- Estimated cathinone content of 0.9 mg/g

- Estimated dosage: 0.8 to 1 mg/kg for cathinone

- Results

- Cathinone is barely detected at 0.5 and 7.5 hours after treatment

- Peak plasma levels obtained after 1.5 to 3.5 hours; maximum levels in the individuals ranged from 41 to 141 ng/mL (mean 83 ng/mL)

(Guantai, 1983) – Metabolism to d-Norpseudoephedrine (cathine) in humans

- 4 volunteers; khat-naive

- Given 16 mg of cathinone extracted from C. edulis in two cases; other two received synthetic cathinone

- Urine collected to look for metabolites

- No significant variation in excretion pattern between volunteers.

- Results confirmed a large portion in humans is metabolized to d-norpseudoephedrine and possibly two other unidentified metabolites

- Basically no cathinone itself is excreted by 15 hours, while d-norpseudoephedrine can still be found.

(Sporkery, 2003) – Examining cathinone and other alkaloids in the hair of Yemenite khat users

- 24 khat users

- All compounds (cathinone, cathine, and norephedrine) were found in 23/24

- Concentrations:

- Cathine: 0.57 to 23.9 ng/mg

- Norephedrine: 0.19 to 25.0 ng/mg

- Cathinone: 0.11 to 22.7 ng/mg

- Highly significant correlation between the self-reported amount of use and the concentrations of cathine and norephedrine.

History

Early history

The origins of the plant are disputed. The most popular hypothesis is that it was first used around Ethiopia and it spread from the Horn of Africa to Arabia along long-distance trading routes between the Muslim states.

One of the more detailed historical claims is that the Abyssinians (Ethiopians) introduced khat to Arabia between the 1st and 6th centuries during their re-conquest of the country. Sometime before this point they had migrated from Arabia to Africa. Eventually they reportedly returned to southern Arabia, overthrew Himyarite leaders around 300, and settled in the region.

Some sources throughout history have claimed khat use actually started in Yemen.

Most historical sources claim khat has a longer history of use than coffee.

The plant’s history has sometimes been pushed all the way to ancient Egypt and the New Testament. Egyptians reportedly considered it a divine food capable of facilitating humanity’s transcendence into “apotheosis,” making the user god-like.

Ancient Ethiopians are said to have considered it a “divine food” as well.

1000s

Abu Rayhan al-Biruni, a Persian scientist, wrote of khat in “Kitab al-Saidina fi al-Tibb,” a medical and pharmacy work. He described the use of the plant.

1238

Naguib Ad-Din, an Arab physician, distributed khat to soldiers to prevent fatigue and hunger. He wrote of the plant in “The Book of Compound Drugs.”

It was also listed as a cure for depression and melancholia, and it was said to be useful in social settings.

1300s

Sabr Ad-Din, an Arab ruler of Ifat, reportedly used it to quell revolutionary tendencies among the recently conquered subjects in Marade, Ethiopia.

1300s – 1400s

Al-Maqrizi, an Egyptian historian and geographer, talked about the use of khat by the people of Zeyla in Somalia or Ethiopia. [Zeyla refers to the Zeyla Federation. I’ve been unable to determine the exact location covered by the Federation. The old city “Zeila” is in Somalia, while the Federation covered ancient areas of Ethiopia, according to some reports.]

[They chewed] the leaves of a plant which enhances intelligent performances, produces appreciable sense of hilarity while depressing appetites for food and sex and repelling sleep.

1587

Abd al Kadir mentioned khat in a manuscript.

The work claimed that a mufti in Aden, Sheik Gemaleddin Abou Muhammad Bensaid, introduced coffee to Aden (Yemen) from Ethiopia in 1454.

Coffee was then adopted by lawyers, students, and artisans in Yemen. Those same people had become fans of a different drink made from khat leaves.

1762

Peter Forsskal, a Swedish physician and botanist, became the first to classify Catha edulis. He discussed the plant in “Flora Aegyptiaca-Arabica.”

Another European, Carsten Niebuhr, a geographer and traveler, also described the plant.

Both had been sent by Frederick V of Denmark on a scientific expedition of the East, specifically Egypt and Arabia.

1800s

Ernst von Bibra, a German naturalist, wrote that coffee largely replaced khat in Yemen once it was introduced. Khat tea and chewing were present in Yemen, and the leaves would either be taken fresh or sun-dried before use.

In the case of khat tea, boiling water or milk would be used, with honey added as a sweetener. For both chewing and tea, “only the most tender leaves or buds are taken.”

Chewing was described as a “great luxury.”

If any distinguished stranger arrived, he would immediately be offered khat, and some of it would then be sent to his residence. Fresh leaves are apparently more popular, and great effort is taken to keep them in this condition by carefully wrapping young branches with the most tender shoots in banana leaves.

Von Bibra also commented on a statement by Antoine Isaac Silvestre de Sacy, who said khat had been used much longer than coffee in Arabia.

In describing the effects of the plant, these descriptions were given by Von Bibra:

People who take khat become cheerful, talkative, and wide awake. Some people also fall into pleasant dreams.

Khat more closely resembles coffee than those more violent excitants [hashish and opium], although it is stronger than coffee.

1800s

Louis Lewin, a German pharmacologist, wrote about khat in “Phantastica.”

Effects:

The kat-eater is happy when he hears everyone talk in turn and tries to contribute to this social entertainment. In this way the hours pass in a rapid and agreeable manner. Kat produces joyous excitation and gaiety. Desire for sleep is banished, energy is revived during the hot hours of the day, and the feeling of hunger on long marches is dispersed. Messengers and warriors use kat because it makes the ingestion of food unnecessary for several days.

Lewin wrote about Georg Schweinfurth’s encounters with khat in Yemen. Schweinfurth, a German botanist and explorer of East Central Africa, had written to Lewin.

When during my travels in Yemen I saw the high, many-storied houses of the mountain villages late at night brilliantly illuminated, and their windows shining in the darkness, I enquired what the inhabitants did at that time of the night. I was told that ‘friends and acquaintances meet and sit for hours round the brazier drinking their coffee prepared from the husks and chew their indispensable kat, which keeps them awake and promotes friendly intercourse.

According to Lewin, khat was used in Yemen prior to coffee. Writing about its history, he said:

The use of kat has become a permanent custom. Originating in Abyssinia, where it was mentioned for the first time in the year 1332, the plant penetrated into Yemen and other parts. There is no doubt that kat was consumed a long time before the date indicated, and will continue to be used in the future, for excitants of the brain defy the lapse of time.

As of the 1800s, the chewing of khat was “quite unknown in Hedjaz and in Jeddah.” Those are two locations in Saudi Arabia.

Usage of khat:

The fresh green points of the leaves, and the shoots of the leaves and stems are eaten, and it is only in Arabia that an infusion of the plant is prepared.

There was a great desire for the drug and social integration of it:

The passion for the drug is so great that even material sacrifices are made in order to indulge in it. There are epicures in Hodeida, Mocha, and Aden who spend two dollars a day on kat. An explorer reported that the Sheikh Hassan of Yemen consumed more than 100 francs worth of kat per day because he was accustomed to have many distinguished visitors.

In some places, for instance in Harar, the consumption of kat is intimately connected with the observance of prayers.

Some problems were associated with substance, so it wasn’t universally liked:

Schweinfurth told me that in no part of the Mohammedan East had he seen so many bachelors as in Yemen. In other countries of Islam this state is regarded as shameful. In Yemen it was openly stated that inveterate eaters of kat were indifferent to sexual excitation and desire, and did not marry at all, or for economic reasons waited until they had saved enough money. The loss of libido sexualis has been also observed in other inhabitants of these countries.

Mohammedan casuists have frequently discussed the question whether the consumption of kat is contrary to the law of the Koran which prohibits the use of wine and everything that inebriates. Even had they come to the conclusion that kat belongs to those substances, no kat-eater would have renounced his passion.

1852

Vaughan, an English surgeon in Aden (Yemen), brought khat to Europe. He said both khat and coffee were important in the Middle East and were used as alternatives to alcohol.

1854

Abdullah bin Abdul Kadir, a traveler from Malay, described the prevalence of khat chewing in Al Hudaydah, Yemen.

You observed a new peculiarity in this city—everyone chewed leaves as goats chew the cud. There is a type of leaf, rather wide and about two fingers in length, which is widely sold, as people would consume these leaves just as they are; unlike betel leaves, which need certain condiments to go with them, these leaves were just stuffed fully into the mouth and munched. Thus when people gathered around, the remnants from these leaves would pile up in front of them. When they spat, their saliva was green. I then queried them on this matter: ‘What benefits are there to be gained from eating these leaves?’ To which they replied, ‘None whatsoever, it’s just another expense for us as we’ve grown accustomed to it’. Those who consume these leaves have to eat lots of ghee [clarified butter] and honey, for they would fall ill otherwise. The leaves are known as Kad [khat].

1856

Sir Richard Burton, a renowned British explorer, wrote of khat in “First Footsteps in East Africa.”

He said it was introduced to Yemen from Ethiopia in the 1400s.

1887

Fluckiger and Gerock isolated “katin,” an alkaloid from khat leaves, but the structure wasn’t identified.

Their experiments also confirmed the plant didn’t have any caffeine.

1891

Mosso reported the basic fraction of an aqueous extract of khat led to mydriasis in frogs and had a stimulating action on frog heart.

Attempts to bring khat to Europe (1800s to 1900s)

Late 1800s

- Some Europeans tried to create khat-based beverages.

- Others attempted to develop a pharmaceutical preparation to treat various medical disorders.

1910

- Pharmacists in Lyon (France) marketed a pill called Neo-tonique Abyssine for the treatment of nervous disorders.

1913

- W. Martindale, a London chemist, sold preparations and pills based on khat extracts.

Despite these efforts, it failed to become a global commodity. This was partly due to a lack of interest, cathinone’s apparent instability, and difficulties in obtaining the leaves during WW1.

1930

Wolfes, likely working with dried khat leaves, also isolated Fluckiger’s katin. He determined it was d-norpseudoephedrine, now known as cathine.

1935

Two reports on the issue of khat usage were released by the Advisory Committee of the League of Nations on the Traffic of Dangerous Drugs.

1949

Jewish Yemenites brought khat to Israel.

Mid-1900s

For a while, cathine was believed to be the main active drug in khat, though some authors quickly pointed out its potency wasn’t significant enough to make sense.

1963

Friebel and Brilla identified a new alkaloid from fresh khat leaves. It was substantially more potent than cathine in stimulating motor activity in mice. It couldn’t be found in dried leaves, so it was suggested the new alkaloid converted to cathine during drying.

1971

The UN Commission on Narcotic Drugs directed the UN Narcotics Laboratory to reinvestigate the chemical composition of khat. Multiple studies came out of that order, eventually leading to the isolation of S-(-)-a-aminopropiophenone from khat leaves.

1975

S-(-)-a-aminopropiophenone was isolated and given the name “cathinone.”

1978 – 1979

Schorno determined cathinone’s absolute configuration, finding it’s a ketone congener of cathine.

1970s and 1980s

Once cathinone was found to be the active drug in khat, pharmacology studies began. They were initiated by an advisory group of the World Health Organization.

Those studies confirmed it had amphetamine-like effects in vitro and in animals.

1982

Schorno looked at the distribution of the alkaloids in fresh khat of various origins and in different parts of the plant.

In certain khat samples, the phenylalkylamine fraction consisted of up to 70% cathinone. And the cathinone content correlated with the market value.

It was determined cathinone is probably a biosynthetic intermediate that tends to accumulate in young, not adult, leaves. In adult leaves, it’s converted to around 4/5 cathine and 1/5 norephedrine. This conversion was also suggested to potentially occur during drying.

1993

The DEA classified cathinone as a Schedule 1 substance.

Yet, only a few years prior it believed the substance was unappealing to Western users.

1998

As part of a UNODC study on illicit drug trends in Africa, research was conducted in Ethiopia. That research found khat cultivation was widespread, financially attractive, and spreading to new areas.

2006

The DEA executed Operation Somali Express. It was the culmination of an 18-month investigation that led to the takedown of a 44-member trafficking group responsible for bringing 25 tons of khat from the Horn of Africa to the US.

The group’s khat had an estimated value of $10 million.

Recent/Current

Cathinone itself has still seen very little use outside of khat.

Khat use

Khat remains very common in parts of the Middle East and Africa. It’s used in Somalia, Yemen, Ethiopia, and Kenya, among other locations.

It’s estimated there are 5 – 20 million daily users.

In Yemen, up to 60% of males and 35% of females use the drug. At least one episode of use has been reported by 81.6% of males and 43.3% of males. It’s estimated 40% of the country’s water supply goes to khat irrigation.

In Somalia, 20 tons of khat worth $800,000 were imported daily from Kenya prior to a ban from the Supreme Islamic Courts Council. After the ban went away, the trade of khat just in Hargeisa, Somalia was reported to be worth $300,000 per day.

Expansion to new regions

Khat has expanded into the West due to its use by immigrant communities, such as Somalis in upstate New York and the UK. Though there’s now a lot of evidence supporting its use in the West, it hasn’t really been used outside of immigrant populations.

In the UK, estimates place the use of khat among Somalis at 37% to 78%.

Officials in the US began associating the plant with terrorism and crime in the 2000s. One DEA official made this statement in 2007:

It is not coffee. It is definitely not like coffee. It is the same drug used by young kids who go out and shoot people in Africa, Iraq, and Afghanistan. It is something that gives you a heightened sense of invincibility, and when you look at those effects, you could take out the word “khat” and put in “heroin” or “cocaine.”

Legal Status

US

Schedule 1

International

Schedule 1

Other

Canada: Schedule 4

UK: Schedule 1

Safety

The safety profile of cathinone is similar to amphetamine. Using too much, either with a high frequency or high doses, can lead to psychological (anxiety, mania, etc) and cardiovascular problems.

Cardiovascular

It reliably causes vasoconstriction, increased blood pressure, and increased heart rate. Typically these effects aren’t an issue for healthy people at normal doses, but they can become a problem with high doses or in susceptible individuals.

Because of the cardiovascular effects, overdoses come with a higher risk of stroke, cerebral hemorrhage, and myocardial infarction.

(Jayed, 2016) – Impact on cardiac arrhythmia in normal and patient populations

- 60 people: 30 cardiac patients, 30 normal individuals

- Cardiac patients had mild/moderate cardiac symptoms (excluded emergency and life-threatening patients)

- Vetricular extrasystoles

- More common on khat-chewing vs. non days for all groups

- Significantly more common among cardiac patients vs. normals

- Isolated ventricular ectopy

- Cardiac

- 27/30 developed ventricular ectopy on khat days

- 13/30 developed ventricular ectopy on non-khat days

- Normal

- 12/30 developed ventricular ectopy on khat days

- 3/30 developed ventricular ectopy on non-khat days

- Cardiac

- Frequent ventricular ectopy

- Cardiac

- 21/30 developed frequent ventricular ectopy on khat days

- 7/30 developed frequent ventricular ectopy on non-khat days

- Normal

- 8/30 developed frequent ventricular ectopy on khat days

- 1/30 developed frequent ventricular ectopy on non-khat days

- Cardiac

- Complex ventricular ectopic beats and couplets

- Cardiac

- 22/30 developed ventricular couplets on khat days

- 9/30 developed ventricular couplets on non-khat days

- Normal

- 6/30 developed ventricular couplets on khat days

- 0/30 developed ventricular couplets on non-khat days

- Cardiac

- Non-sustained ventricular tachycardia

- Cardiac

- 7/30 developed non-sustained ventricular tachycardia on khat days

- 2/30 developed non-sustained ventricular tachycardia on non-khat days

- Normal

- 1/30 developed non-sustained ventricular tachycardia on khat days

- 0/30 developed non-sustained ventricular tachycardia on non-khat days

- Cardiac

- Interpretation

- Correlation in both normal and cardiac groups between khat chewing and arrhythmias.

- The source of triggering or aggravating ectopic impulse generation remains unclear.

(Al-Motarreb, 2005) – Association between khat use and acute myocardial infarction

- Comparing 100 cardiac patients to 100 non-cardiac patients in Yemen

- Khat chewing was significantly more common in cardiac group (89% vs 69%)

- Mild users didn’t have a higher risk, moderate users were shown to be at a high risk, and heavy users had an even higher risk, indicating dose-dependency.

- Based on the amount of khat per session.

- Similar correlation found in those who reported session durations greater than 4 hours.

Case reports

(Kulkarni, 2012)

- 47-year-old male originating from Sanaa, Yemen

- No history of diabetes, hypertension, or ischemic heart disease.

- Regular khat user for 30 years

- Taking around 500 – 600 grams per day over 6-8 hours.

- Presented with sudden onset left-sided weakness with deviation of mouth to the right side.

- Examination

- Conscious, oriented, and normal temp.

- HR of 80

- BP of 200/100

- Left-sided hemiplegia

- Left-sided upper motor neuron facial palsy

- Diagnosis

- Left hemiplegia due to right middle cerebral artery infarction

- Treated for ischemic stroke, told to discontinue khat, and given antihypertensive.

- Patient gradually recovered over months, reaching left limb strength of 4/5 at 6 months.

- Khat was considered the cause given the lack of other high-risk factors.

Animal studies

(Admassie, 2011) – Looking at impact of khat extracts on cardiac biomarkers, necrosis, and BP

- Rats

- Bundles of fresh khat leaves and small branches from Ethiopia (Aweday) used for extract.

- 100, 200, and 400 mg/kg groups

- Given orally

- Some tests acute (e.g. BP) and others subchronic (six weeks of dosing)

- Results

- Acute BP

- Failed to detect difference in the BP vs. predose level for 100 and 200 mg/kg.

- Significant rise in 400 mg/kg group for SBP, DBP, and MBP.

- This change was also significantly higher than the lower dosage impact.

- Subchronic effect on cardiac biomarkers

- Levels of total CK increased significantly at all doses

- 100 mg/kg: 38.8%

- 200 mg/kg: 66%

- 400 mg/kg: 93.9%

- AST

- Significantly higher for 200 mg/kg (7.2%) and 400 mg/kg (58.2%)

- cTnT

- Undetectable in controls; increased with dose from khat groups

- Yet, some of the rats in the 100 and 200 mg/kg groups didn’t have detectable cTnT levels either.

- 400 mg/kg led to consistently higher levels of cTnT and significantly greater values vs. control, 100 mg/kg, and 200 mg/kg.

- Undetectable in controls; increased with dose from khat groups

- Levels of total CK increased significantly at all doses

- Morphologic pathology

- No notable changes at 100 mg/kg

- 200 mg/kg

- Normal myocardial architecture

- But signs of focal lesions with mild necrosis

- 400 mg/kg

- Changes in myocardial architecture

- Tissues exhibited subendocardial necrosis, atrophy, more diffuse esinophilia, myocardial structure disorder, and mottled staining.

- Grade 2 on the grading system for myocardial necrosis.

- Marked signs of myocardial infarction.

- Evidence fit with minor cardiac injuries vs. major given the lack of a massive infarct.

- Acute BP

- Interpretation

- High doses of khat extract can significantly raise BP acutely, but not during non-drug times.

- Subchronic use leads to elevation of cardiac biomarkers indicative of myocardial cell death.

Psychological

Manic states and stimulant psychosis could arise from cathinone, especially with heavy acute or chronic use. Overall, both issues are pretty uncommon.

The psychotic states have been reported to include persecutory delusions, auditory hallucinations, fear, and anxiety.

(Tulloch, 2012) – Reviewing khat’s association with the use of South London, UK mental health services

- 240 Somali-born patients were identified

- Khat use known in 172

- 80 were current khat users

- 92 weren’t khat users or were prior users

- Khat associated with

- Male gender, harmful use of alcohol or alcohol dependence, primary diagnosis (higher with a primary diagnosis of schizophrenia, other psychotic illness or drug/alcohol disorder), and having an inpatient stay.

Cognitive

Cathinone can allegedly cause cognitive impairment with heavy long-term use, such as with working memory and cognitive flexibility. But we don’t have much good quality evidence for this.

(Colzato, 2011)

- Compared 20 khat users to 20 khat-free people

- Participants asked to refrain from drug use for 24 hours, but a lack of drug use wasn’t even analytically confirmed.

- Khat users

- 10.5 years

- 3.1 uses per week

- 5.8 hours, on average, per usage day

- Results

- Showed impairments in cognitive flexibility measure and 1-back and 2-back tests, suggesting impairments in working memory.

Oxidative stress

Like other stimulants, it can likely increase oxidative stress. This could be a problem with excessive use since it can eventually damage cells, including neurons.

Studies

(Safhi, 2014)

- Mice

- 4 groups

- 1 control

- 3 receiving either 0.125, 0.25, or 0.5 mg/kg IP cathinone

- Given once per day for 15 days

- Studying impact specifically on the limbic area of the mouse brain

- Results

- Lipid peroxidation and glutathione

- Content of TBARS (lipid peroxidation marker) increased dose-dependently; significant effects at 0.25 and 0.5 mg/kg

- Content of glutathione dose-dependently decreased; significant effects at 0.25 and 0.5 mg/kg

- Antioxidant enzymes

- Activity of glutathione peroxidase, glutathione reductase, superodixe dismutase, and catalase

- Dose-dependently reduced; depletion significant at 0.25 and 0.5 mg/kg

- Glutathione also decreased dose-dependently with a significant decline at 0.5 mg/kg

- Activity of glutathione peroxidase, glutathione reductase, superodixe dismutase, and catalase

- Lipid peroxidation and glutathione

- Interpretation

- Cathinone can, at relatively low doses, result in a reliable increase in limbic region oxidative stress, which could damage cells.

Case series

(Bentur, 2008) – Involving actual synthetic cathinone

- Capsules of Hagigat in Israel

- Analyzed by police and found to contain 200 mg of cathinone.

- Background

- End of 2003

- Hagigat showed up on the market as an alternative to khat.

- Capsules labeled, “Natural stimulant and aphrodisiac for men and women, contains no chemicals; drink fluids liberally.”

- September 2004

- Sporadic consultations pertaining to Hagigat exposure reached the Israel Poison Information Center.

- November 2004

- Ministry of Health issued a public alert about the products.

- Cases

- 34 people from September 2004 to June 2005

- 33/34 were symptomatic

- Admission

- 15/34 needed observation and treatment in ED

- 10/34 were admitted (3 to intensive coronary unit and 1 to neurosurgical ward)

- 5 could be managed in a community clinic.

- Patients

- Age: 25 median

- ROA

- 27 had intact oral capsule

- 5 had powder from capsule orally

- 2 intranasally used powder

- Dose

- Median of 2 capsules (0.5 to 6)

- Single, not repeated, exposure in 30 cases

- Time to clinical manifestation

- Median of 3 hours (30 min to 6 hours)

- Treatment was mainly supportive: benzodiazepines, analgesics, vasodilators, diuretics, oxygen, and mechanical ventilation.

- Though one needed neurosurgical intervention for intracerebral hemorrhage.

- GC-MS confirmed the exclusive presence of cathinone in a capsule obtained from one of the patients.

- Resolution of symptoms

- Follow-up unavailable in 15

- 8 reported full resolution within 24 hours

- 11 reported headache lasting up to seven days

- Total symptoms

- Neuropsychiatric

- 17 headache

- 4 restlessness

- 4 dizziness

- 2 anxiety

- 1 intracerebral hemorrhage

- Cardiovascular

- 9 hypertension

- 7 tachycardia

- 6 chest pain

- 5 bradycardia

- 3 palpitations

- 3 ischemic ECG changes

- Respiratory

- 7 dyspnea

- 2 pulmonary edema

- Misc

- 11 vomiting

- 8 nausea

- Severe cases

- The intracerebral hemorrhage involved left hemiplegia in a previously healthy 28-year-old female

- 3 patients with ischemic changes on ECG showed inverted T waves, depressed ST segments, and elevated serum troponin.

- Mechanical ventilation required for 25-year-old female and 16-year-old male

- Both had ischemic ECG changes, elevated troponin, and reduced ejection fraction (10-20%)

- Neuropsychiatric

References

(2016) Khat Chewing Induces Cardiac Arrhythmia

(2015) Khat Use: What Is the Problem and What Can Be Done?

(2014) Neurobiology of Khat (Catha edulis Forsk)

(2012) Khat and stroke

(2012) Khat use among Somali mental health service users in South London.

(2011) An Overview of Khat

(2011) Chemistry, Pharmacology, and Toxicology of Khat (Catha Edulis Forsk): A Review

(2011) Khat use is associated with impaired working memory and cognitive flexibility.

(2011) Chemistry, pharmacology, and toxicology of khat (catha edulis forsk): a review.

(2010) Cathinone preservation in khat evidence via drying.

(2010) Khat in the Horn of Africa: historical perspectives and current trends.

(2009) Khat – a controversial plant.

(2008) A review of the neuropharmacological properties of khat.

(2008) Illicit cathinone (“Hagigat”) poisoning.

(2006) What harm? Kenyan and Ugandan perspectives on khat

(2005) Khat chewing is a risk factor for acute myocardial infarction: a case-control study.

(2003) Determination of cathinone, cathine and norephedrine in hair of Yemenite khat chewers.

(2003) The toxicological potential of khat.

(2002) Effect of khat, its constituents and restraint stress on free radical metabolism of rats.

(1996) Catha edulis, a plant that has amphetamine effects.

(1995) Plasma cathinone levels following chewing khat leaves (Catha edulis Forsk.).

(1991) Khat and oral cancer.

(1989) Potentiation of cathinone by caffeine and nikethamide.

(1988) Khat-induced hypnagogic hallucinations.

(1986) Metabolism of cathinone to (−)-norephedrine and (−)-norpseudoephedrine

(1986) Khat: Another Drug of Abuse?

(1985) Quantitative differences in the pharmacological effects of (+)- and (−)-cathinone

(1984) Recent advances in khat research.

(1983) Metabolism of cathinone to d-norpseudoephedrine in humans.

(1982) Cardiovascular effects of (−)-cathinone in the anaesthetized dog: comparison with (+)-amphetamine

(1980) Hyperthermic response to (-)-cathinone, an alkaloid of Catha edulis (khat).

(1979) Research on the chemical composition of khat.

(1947) Khat