Bupropion is an antidepressant and a smoking cessation aid. The drug has been tested in many other conditions, including ADHD, obesity, and seasonal affective disorder.

It has multiple pharmacological mechanisms and it’s still not entirely clear how bupropion works.

Some recreational use has been reported, though the substance usually isn’t very pleasant and it can be dangerous.

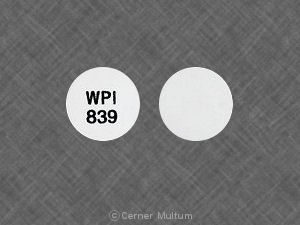

Bupropion = Amfebutamone; Wellbutrin; Zyban; Quomen; Zyntabac; Budeprion

PubChem: 444

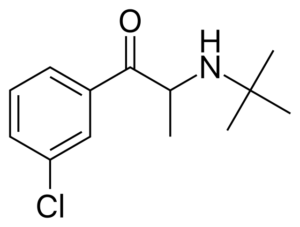

Molecular formula: C13H18ClNO

Molecular weight: 239.743 g/mol

IUPAC: 2-(tert-butylamino)-1-(3-chlorophenyl)propan-1-one

Contents

Dose

Oral (medical)

Forms

Instant-release (IR): 75 and 100 mg

Sustained-release (SR): 100, 150, and 200 mg

Extended-release (XR/XL): 150 and 300 mg

The dose usually begins low (such as 100 mg) and is increased over a period of weeks. The final chronic dose depends on the patient’s response and what condition is being treated.

Maximum dose (total daily exposure)

SR: 400 mg

IR and XR/XL: 450 mg

Recreational

No reasonably safe dose is going to provide much in the way of recreational effects.

The same maximum dose should be observed. Also, the maximum dose is for an entire day’s administration. This means even 300-400 mg IR at once isn’t wise.

Timeline

Oral (medical)

Total: Depends on the form being used

Onset: Under 60 minutes

It’s used 1-3x per day depending on the form used and the patient’s response. The instant release form may be taken 3x per day, while the extended-release form can be taken just once.

Experience Reports

Effects

Positive

- Stimulation

- Mood lift

- Depression reduction

- Increased focus

Negative

- Tachycardia

- Anxiety

- Paranoia

- Hallucinations

- Seizures

- Dry mouth

- Nausea

- Insomnia

Medical

It’s primarily used for depression and smoking cessation. Some use also exists for ADHD, seasonal affective disorder, and other conditions.

Depression

Efficacy

Studies indicate it is superior to placebo and may take up to 4 weeks for the maximal effect to appear. Treatment usually continues at least for several months.

Some 8-week trials have yielded a 35-40% remission rate, but this will depend on the treatment population.

Not all studies are in agreement about its efficacy. For example, in one review of six studies, only two reported bupropion XR to significantly outperform placebo on the core outcome measure (depression).

When it’s effective, the drug may lead to positive changes on ratings of energy, pleasure, and interest. There can be some accompanying decline in anxiety for some users, but it’s not reliable.

VS other antidepressants

A study looking at patients who didn’t tolerate citalopram or didn’t respond to it found bupropion had a 25% remission rate during a 14-week trial.

Most research suggests its overall efficacy is similar to SSRIs (fluoxetine, sertraline, paroxetine), TCAs (nortriptyline, amitriptyline, doxepin), and trazodone.

Three studies comparing bupropion to venlafaxine (SNRI) didn’t find any significant differences.

A meta-analysis of bupropion vs SSRIs found similar response rates for depression. Bupropion was often superior on measures of drowsiness and fatigue.

Bupropion produces less sexual dysfunction, weight gain, and sedation relative to SSRIs and TCAs. Bupropion has a higher incidence of dry mouth and may also produce more insomnia.

While weight gain sometimes occurs, it’s not as common (relative to SRIs and TCAs) and weight loss is more common.

Compared to trazodone, bupropion caused less drowsiness, less increase in appetite, and a lower chance of edema. It was more likely to have an anorexic effect and to increase anxiety.

Smoking cessation

Bupropion is more effective than placebo at raising the chance of quitting. It’s equally as effective as nicotine replacement therapy (NRT). The effect rate drops once a patient stops taking bupropion. Longer treatment periods (e.g. 6 months vs 7-12 weeks) might be useful in raising the long-term efficacy.

It’s sometimes preferred by tobacco users who dislike the idea of continuing nicotine or who have failed with NRT in the past.

One study found it was superior to minimal counseling but not more effective than intensive psychological counseling.

Bupropion is less effective than varenicline overall and may be less effective than combinations of NRT.

The drug seems to reliably alleviate withdrawal symptoms and reduce craving during abstinence.

Dose-dependency does exist, with 300 mg appearing to be superior to 100 mg.

Treatment continues for a period of months and a nicotine quit attempt is usually made in the second week.

ADHD

It is sometimes used in cases of ADHD. Studies suggest it’s effective for some, though the overall efficacy is lower than what’s seen with methylphenidate and other typical treatments.

Controlled clinical trial

It reduced ADHD symptoms relative to baseline significantly more than placebo.

There was a 52% response rate, which is significant yet lower than what’s typically seen with traditional ADHD drugs.

A 42% reduction in ADHD scores was noted at Week 6, compared to 24% for placebo.

Seasonal affective disorder

Efficacy has been demonstrated in multiple placebo-controlled trials. It outperformed placebo in 3/3 studies examined in a review.

Treatment begins prior to the onset of depressive episodes with the intention of reducing the occurrence of depression.

Addictive behaviors

Studies have looked at its impact on cocaine dependence, pathological gambling, methamphetamine dependence, and even video game addiction.

For cocaine, a possible benefit was seen and a study suggested there was a greater effect in those with higher comorbid depression. Some research has found it doesn’t reliably lead to reduced craving and isn’t very effective at reducing use.

Video game addiction

Bupropion SR was examined in a group of patients with an addiction to video games. In those individuals, a rise in activity in certain parts of the brain, such as the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC), is seen in the presence of gaming-related stimuli.

Bupropion reduced the DLPFC activity and was associated with reduced maladaptive behavior patterns pertaining to gaming.

Other

Obesity

One study with 50 women found it might be useful relative to placebo in cases of obesity. The efficacy may have at least partly come from better diet compliance in the bupropion group.

Treating SRI-induced sexual dysfunction

It’s sometimes used in clinical practice when sexual dysfunction is present during SSRI or SNRI therapy. There is evidence that it can reduce measures of sexual dysfunction, thereby resulting in a rise in sexual desire and related measures.

Altering SRI therapy

Studies have provided contradictory efficacy levels for bupropion combined with SSRIs. However, the combination tends to be better than continued monotherapy in those who lack an adequate response to their SSRI or SNRI.

Combining them does appear to raise the chance of seizure and serotonin syndrome.

TNF-a activity

There’s some evidence from humans and animals that it inhibits TNF-a and could therefore be useful in some inflammatory conditions. Reports exist of it helping with Crohn’s disease and aphthous ulceration.

Negatives

The primary negatives in medical settings are dry mouth, insomnia, agitation, and dizziness. Some patients find it leads to a jittery, overstimulated, or otherwise uncomfortable feeling, which is a common reason for treatment to be stopped.

It’s not associated with a significance rise in neuropsychiatric or cardiac problems.

Seizures are the primary severe medical concern and they’re dose-dependent. 450 – 600 mg is much riskier than 300 – 450 mg, for example.

Many overdoses include seizures and they’ve even been reported in medical settings. The risk is low in patients with no risk factors if they begin at a sub-maximum dose and don’t exceed the max dose during treatment.

Recreational

The most popular claim about its effects is that it’s reminiscent of a very weak cocaine-like effect when take intranasally. Some recreational effects have been reported at high oral doses as well.

A lot of people find it never becomes recreational, however. It often just produces a state filled with tachycardia, anxiety, and tremor.

It’s primarily taken due to accessibility. People may be prescribed the drug and have it on hand or know someone who has a prescription. Many chronic users have a prior substance use disorder.

At most, bupropion offers a light form of stimulation and mood lift for about an hour (intranasal). The maximum daily dose should never be exceeded nor should it be reached with a single administration.

2002 study

It was found that in patients with a substance abuse history, 400 mg oral could yield some mild amphetamine-like effects.

Case reports

Case 1

- 13-year-old female

- Took 600 mg oral

- Told it would be better than amphetamine

- No adverse effects noted

Case 2

- 16-year-old male

- 900 mg of bupropion SR intranasally

- Developed a seizure

- Reported a brief “buzz” from taking the crushed tablets on prior occasions

- Friends also used it

Case 3

- 15-year-old female

- Prescribed for ADHD, but ended up using it recreationally and diverting tablets to friends.

- She reported a “buzz” that only lasted a matter of seconds.

Case 4

- 44-year-old male

- History of polysubstance dependence

- Learned about intranasal bupropion use during a single night in jail.

- He crushed and used the drug after he was released.

- The use led to a “high” that lasted up to 30 minutes.

- Reported to be “only about 20% of cocaine’s high.”

- He would use up to seven 300 mg bupropion tablets.

- Only the first one or two got him “high.”

Chemistry & Pharmacology

Chemistry

Bupropion is a monocyclic aminoketone that’s structurally distinct from SSRIs and TCAs.

Some of its structure is shared with phenethylamines and amfepramone.

Pharmacology

The mechanisms of action aren’t fully understood. Two key components appear to be dopamine/norepinephrine reuptake inhibition and antagonism of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors.

Its metabolism plays a role as well, as multiple active drugs are produced, in particular hydroxybupropion. Some of the research has been complicated by significant differences in bupropion metabolism between rats and humans. Mice and guinea pigs appear to be better test subjects for this reason.

Monoamine reuptake inhibition

Bupropion inhibits the reuptake of dopamine and norepinephrine. It may also affect the release of both.

- IC50 values

- NET: 1.37 uM

- DAT: 1.64 uM

- SERT: 28.69 uM

Nicotinic antagonism

Bupropion antagonizes nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, including a3b2, a4b2, and a7. It’s most potent at a3b2 and least potent at a7.

The antagonism is affecting receptor subtypes associated with dopamine and norepinephrine release. Bupropion may also antagonize nicotine-evoked dopamine activity.

Nitric oxide & cGMP

Some research suggests a connection between antidepressant activity and modulation of nitric oxide.

One study found nitric oxide synthase (NOS) inhibitors, including methylene blue, could raise extracellular levels of serotonin and dopamine in rats.

Bupropion study

Bupropion in mice can dose-dependently reduce the immobility period in depression tests with an ED50 of 18.5 mg/kg (IP). It also increases locomotor activity.

A rise in dopamine and its metabolite, homovanillic acid, was noted in mouse brain. Over 20 mg/kg raises norepinephrine.

Pretreatment with l-arginine, a nitric oxide precursor, reversed the beneficial effect of bupropion on the immobility period. While 7-nitroindazole, a NOS inhibitor, boosted the beneficial effect of lower-dose bupropion. Methylene blue had the same effect as 7-nitroindazole.

It was hypothesized bupropion was ultimately helpful due to it decreasing cGMP levels. This is due to its effect also being antagonized by sildenafil, a PDE5 inhibitor. PDE5 plays a role in intracellular cGMP concentrations.

Altering nicotine tolerance and withdrawal

Multiple actions may contribute to bupropion’s ability to reduce nicotine use. A study in mice shed light on some of its nicotine-related activities.

Bupropion reversed chronic tolerance to nicotine-induced antinociception (tail flick test) at 20 mg/kg, but not 1 mg/kg. Hydroxybupropion achieved the same with 5 mg/kg, though not 1 mg/kg.

A dose-dependent reversal of tolerance to nicotine-induced hypothermia was also recorded with both drugs.

Mechanisms

Two core mechanisms were proposed.

First, it may reverse tolerance via nicotinic antagonism. Bupropion and hydroxybupropion antagonize nACh receptors that mediate nicotine-induced antinociception and hypothermia. Those receptors also play a role in the reward mechanisms of nicotine and may be connected to withdrawal symptoms.

Second, nicotine may cause adaptive pre or post-synaptic noradrenergic changes. If so, greater norepinephrine activity from bupropion and hydroxybupropion could combat some aspects of withdrawal that are dependent on noradrenergic adaptations.

CYP2D6

It inhibits CYP2D6, leading to interactions with certain other drugs. Interactions caused by this activity have shown up in the literature.

The inhibition is significant enough to raise the chance of adverse effects or alter the efficacy of other drugs.

Metabolites

Hydroxybupropion is significantly more biased towards norepinephrine overall. S,S-Hydroxybupropion is similar to bupropion with its monoamine reuptake inhibition, however.

S,S-Hydroxybupropion is also more potent as an a4b2 nACh antagonist and it alleviates nicotine withdrawal in mice with a greater potency than bupropion.

Hydroxybupropion can decrease the firing rate of noradrenergic neurons in the locus coeruleus. The action is inhibited by yohimbine, an a2 adrenergic antagonist. Animal studies have found the dose required for this dampened noradrenergic activity is correlated with antidepressant action.

Pharmacokinetics

IR Tmax: 1.5 to 2 hours

SR Tmax: 3 hours

XR Tmax: 5 hours

Half-life: Around 21 hours with chronic use

The core metabolites are hydroxybupropion, threohydrobupropion, and erythrohydrobupropion. Their half-lives are around 20-30 hours or greater and they accumulate more with chronic use.

Hydroxybupropion’s steady-state concentration is 7 to 10 times higher than bupropion’s.

Its primary metabolic route is through CYP2B6, which leads to hydroxybupropion. Other mechanisms lead to the other metabolites.

History

1969

Nariman Mehta, a chemist who was working for Burroughs Wellcome, synthesized the drug. They were looking for a new antidepressant.

1970s

Testing began in the 1970s and the in vivo effects were reported to be different from amphetamine in 1977.

1980s

The FDA granted approval to bupropion for depression in late 1985. It was quickly withdrawn from the market due to concerns about its seizure potential.

A notable seizure risk appeared in a study involving bulimic patients. When further research occurred, it was clear the drug could be used safely if more care was taken.

It reentered the US market in 1989 as an antidepressant. The dosing was adjusted downward due to the realization than under 450 mg only had a small connection to seizures.

1980 – 1990s

Dr. Linda Ferry (and others) noticed that depressed patients given bupropion would sometimes spontaneously reduce or quit tobacco.

Controlled trials in non-depressed people supported its efficacy as a smoking cessation aid.

It was approved for smoking cessation in 1997 under the name Zyban, a sustained-release form of the drug. This made it the first pharmacotherapy for tobacco addiction other than nicotine in the US.

1998 – 1999

Bupropion accounted for 5% of all antidepressant medication exposures reported to the US’ Toxic Exposure Surveillance System (TESS).

Early 2000s

A bit of attention was given to the drug’s use in tobacco addiction as well as its use in ADHD. Prescribing was taking place for ADHD in minors.

2000s

More reports of recreational use showed up, often with it being used intranasally. Some of the cases involved people who had been prescribed the drug, including adolescents given the drug for ADHD.

One location where it’s been used to a notable degree is in some prisons.

The XL formulation was approved in 2003 and entered the market in 2004.

A warning about possible severe neuropsychiatric problems with antidepressants including Bupropion was issued by the FDA in 2004. The FDA extended its warning to cover its use in smoking cessation in 2009.

The warning followed a few dozen reports of suicidal ideation and suicidal behavior between 1997 and 2007. Though, it wasn’t (and isn’t) clear that there’s a particularly concerning connection between bupropion and suicidal activity.

2007

It was reported to be the top smoking cessation aid in the US. An estimated 8.7 million prescriptions were being dispensed annually.

Mid 2000s – 2010s

A rise in recreational use seemed to be recorded, including a number of reports of intravenous (IV) administration. IV use was connected to a few cases of tissue damage.

Most of the chronic use reports have involved people who previously had another substance use disorder. It’s still not a particularly common recreational drug.

Legal Status

US (as of January 2017)

Unscheduled, though it’s only available with a prescription.

Other countries

It tends to be unscheduled. It might be prescription-only depending on the country.

Safety

Typical medical doses aren’t associated with severe medical concerns in otherwise healthy people. But the drug does have a narrow safety range given its seizure risk.

Overdose

The most common overdose symptoms are agitation, stimulation, tachycardia, nausea, vomiting, seizures, hallucinations, and tremor. Tachycardia is typically the only cardiac problem, though cardiac conduction delays have been noted on a few occasions.

One review found tremor occurred in 7.1 to 24% of overdoses.

Over 1 gram produces the most severe effects, but overdose symptoms can appear in the hundreds of milligrams.

Seizures

Seizures are the most common severe medical problem associated with bupropion overdose. The risk is fairly low at common therapeutic doses, yet it becomes quite high in overdose. Seizures are more likely when the drug is combined with stimulants.

The onset can be delayed up to 12+ hours, though the onset is almost always under 12 hours (often under 6) with IR use.

Even 150 to 450 mg may lower the seizure threshold, which is a problem for susceptible individuals. The median seizure dose is over 1-2 grams.

Reports

Report 1

- US Toxic Exposure Surveillance System (1998 – 1999)

- Found 6% of accidental/intentional overdoses led to seizures.

- IR use had a greater correlation to seizures than SR.

Report 2

- Analysis of 385 intentional overdoses reported between 1998 and 1998.

- Seizures occurred in 11% of cases.

- The rate increased to 41% when only looking at cases with other clinical effects.

- Onset: Mostly under 6 hours.

- Dose: More common over 2.5 grams

Report 3

- Analysis of dozens of overdose cases

- Mean dose for seizures: 3078 mg

- Range: 575 – 6000 mg

Report 4

- Found to mainly occur with monodrug use and over 600 mg.

- Occurred in 37 patients (31.6%)

- Onset: Ranged from 0.5 to 24 hours

- It was under 8 hours in 25/37 patients

- Tachycardia, agitation, and tremor were more common in those with seizures.

Report 5

- Australian review

- Found 37% of overdoses resulted in seizure

- Mean dose for seizures: 4.8 grams

Report 6

- Analysis of 385 cases of intentional overdose

- Seizures in 41 (11%) of cases

- Dose range: 600 mg to 18 grams

- Most common in those who took over 2.5 grams or those who used other stimulants.

- Nearly all those who had seizures also had a prodrome of neurological symptoms

- Agitation, tremor, and hallucinations

- There was one atypical case of delayed onset

- First seizure at 9 hours

- No prodrome

- Took 6.75 grams of bupropion XR

Psychosis and hallucinations

Both psychosis and hallucinations have occasionally been reported in medical settings. Hallucinations are fairly often seen with significant overdoses.

The symptoms include visual hallucinations (e.g. figures walking around), auditory hallucinations (e.g. voices), severe agitation, and disorientation to time. There’s at least one report where the hallucinated voices were suggesting self-harm.

These problems may be more common when over 400 mg/d is used. Some patients have encountered issues after a dose increase and reported a resolution of symptoms when their dose was lowered.

Problems in clinical settings

There’s a very low rate of serious adverse reactions (SARs) and death with the therapeutic use of bupropion.

When SARs develop, they usually occur within the first 14 days of treatment. That timeline fits with the time it would take for steady state to appear after a dose increase early in the second week.

The most common SARs are seizures, angiodema, and serum thickness-like reactions.

A few rare cases of bullous eruption have been recorded.

- One review

- 9 cases

- 6 cases of erythema multiforme

- 3 cases of Stevens-Johnson Syndrome

- 9 cases

Hepatotoxicity

This has only been reported on a few occasions in patients and at very high doses in animals with prolonged administration. It’s been nearly absent from clinical tests.

One review found at least 3 instances of hepatotoxicity, one of which led to death. All cases developed within the first 6 months of treatment.

Case report (2005)

- 55-year-old male

- Prescribed bupropion for smoking cessation

- Also taking warfarin and paroxetine.

- Taking 150 mg/d for 6 months

- Reported easy bruising, jaundice, fever, nausea, vomiting, and fatigue.

- He ended up dying from acute liver failure.

- There was extensive necrosis and shrunken liver.

- Bupropion was blamed, not the warfarin or paroxetine, both of which were being used before bupropion.

Risky combinations (list may not be complete)

Other stimulants, MAOIs, ethanol, and tramadol.

It’s also wise to avoid psychedelics and ibogaine.

Overdoses

Case 1

- 14-year-old male

- Prescribed it for ADHD

- No history of seizures or other medical conditions

- Took 15 to 30 tablets of 100 mg in a suicide attempt

- Reached ED five hours after administration

- Visual hallucinations, tachycardiac at 130

- He had at least two tonic-clonic seizures at hospital

- Confused, drowsy, slight ataxia, impaired movement, though responsive to voice and touch.

- 18 hours post-administration

- Short period of extreme agitation and combativeness

- Remained confused and disoriented until 24 hours post-administration=

- Urine screen

- Bupropion and cannabinoids

Case 2

- 10-year-old female

- Prescribed 100 mg for ADHD

- Seizures

- She was also receiving guanfacine

Case 3

- 18-year-old female

- Intentional use of 9 grams

- Single tonic-clonic seizure

- Responsive to diazepam

Case 4

- 23-year-old Taiwanese male

- Prescribed 300 mg SR (initially 150 mg) and midazolam (7.5 mg) for depression and other psychiatric symptoms

- Attempted suicide

- 4200 mg of bupropion

- 105 mg of midazolam

- Presented at ED 6 hours post-administration

- Drowsy, but responsive to vocal commands

- Also depressed

- 12 hours post-administration

- Irritable mood, psychomotor agitation, wandering, aggressive towards staff

- Delusional

- Claimed psychiatric ward wasn’t real, that he was kidnapped, and that people had stolen his money.

- He believed his paranoid delusions and was aggressive because of them.

- Paranoid thoughts (but no hallucinations) continued for 2 days

Case 5

- 29-year-old male

- 5 days of therapeutic bupropion at 300 mg SR

- Taken for nicotine withdrawal

- Led to acute psychosis and blurry vision

- Visions of the Revelation of St. John, Hitler, and the Antichrist

- Paranoid

- “Extraterrestrians may be installing certain devices on Earth.”

- He was also a heavy nicotine, alcohol, and cannabis user.

- But his use hadn’t changed around the incident.

Case 6

- 16-year-old female

- Took 1.5 grams of bupropion SR

- Brought to ED after a seizure

- More seizure activity in the ED

- Intraventricular conduction delay

- Abnormality disappeared without treatment.

Case 7

- 32-year-old male

- Found agitated and tremulous at home

- Appeared to have taken a full bottle of bupropion IR (around 9 grams)

- Developed seizure en route to ED

- At ED

- Agitated and combative

- BP: 115/78

- HR: 155

- Sinus tachycardia

- ECG revealed supraventricular tachycardia of 123

- Prolonged QRS and QTc intervals

- Delirium present for 36 hours

- No further seizures

- ECGs showed resolution of tachycardia by 12 hours and of conduction delays by 48 hours.

Case 8

- 27-year-old female

- Prescribed

- Bupropion XR at 300 mg/d

- Clonazepam at 0.5 mg twice daily

- Lamotrigine at 100 mg/d

- Zolpidem at 10 mg/d

- Six weeks after being on that regimen

- She lost consciousness at work and had a tonic-clonic seizure 2 hours after her daily dose of bupropion.

- Taken to ED

- Had another tonic-clonic seizure 8 hours later

- She was kept on everything but bupropion

- No seizures during next 8 months

Fatalities

Case 1

- 26-year-old male

- 23 grams of bupropion believed to have been taken

- Tonic-clonic seizure after paramedics arrived

- Diazepam ineffective

- Suffered cardiac arrest

Case 2

- 35-year-old male

- Found 72 hours post-death

- Empty box of 30 bupropion SR near the body

- Prescribed for smoking cessation

- Family said he had become increasingly depressed

- No other drugs or alcohol seemed to be involved

Case 3

- 16-year-old male

- Took 9 grams of bupropion SR

- During next five hours

- Agitation, vomiting, and hallucinations

- Seizures began at 6 hours with no return of consciousness between

- EMS arrived and he was in full cardiopulmonary arrest

- Post mortem

- Blood: 5.4 ug/mL

Case 4

- 18-year-old female

- Found in bedroom after full cardiopulmonary arrest and rigor mortis evident

- Vomiting present in a container

- Suicide note found

- 12x 9 mg transdermal selegiline patches had been applied

- 21x relatively intact 300 mg bupropion SR tablets found in autopsy

- Post mortem

- Blood: Over 20 ug/mL

Case 5

- 29-year-old female

- Found in full cardiopulmonary arrest

- Around 6.9 to 7.2 grams estimated to have been taken

- Post mortem

- Blood: 7.0 ug/mL

- Citalopram was also present at 4.0 ug/mL

Case 6

- 36-year-old male

- Took a large number of pharmaceutical tablets directly in front of hospital.

- Quickly taken to ED and given activated charcoal

- Believed to have been exposed to bupropion, metoprolol, ibuprofen, and lamotogrine.

- Initial blood test showed no bupropion

- Seizure activity recorded 12 hours post-administration

- Apneic and failed resuscitation followed

- Post mortem

- Blood bupropion: 3.1 ug/mL

- Blood diphenhydramine: 0.29 ug/mL

- Blood lamotrigine: 3.6 ug/mL

Case 7

- 24-year-old female

- Full cardiopulmonary arrest at home

- Had been seen by family four hours prior

- Post mortem

- Blood: 7.6 ug/mL

References

(2016) Bupropion: a systematic review and meta-analysis of effectiveness as an antidepressant.

(2014) Bupropion abuse and overdose

(2014) Intravenous Administration and Abuse of Bupropion: A Case Report and a Review of the Literature

(2014) Efficacy of interventions to combat tobacco addiction: Cochrane update of 2013 reviews.

(2013) Additional evidence of the abuse potential of bupropion.

(2013) Pharmacological interventions for smoking cessation: an overview and network meta-analysis.

(2013) Intranasal bupropion abuse: case report.

(2012) Bupropion and its main metabolite reverse nicotine chronic tolerance in the mouse.

(2010) Effects of Hydroxymetabolites of Bupropion on Nicotine Dependence Behavior in Mice

(2009) Incidence and onset of delayed seizures after overdoses of extended-release bupropion.

(2008) A fatal case of bupropion (Zyban) overdose.

(2008) Fatal bupropion overdose with post mortem blood concentrations.

(2008) Bupropion: a review of its use in the management of major depressive disorder.

(2008) Bupropion for the treatment of methamphetamine dependence.

(2007) Extended-release bupropion induced grand mal seizures.

(2007) A fatal case of bupropion (Zyban) hepatotoxicity with autoimmune features: Case report

(2007) Stereoselective analysis of hydroxybupropion and application to drug interaction studies.

(2007) Fatigue as a core symptom in major depressive disorder: overview and the role of bupropion.

(2006) Bupropion for the treatment of nicotine withdrawal and craving.

(2006) Bupropion for smokers hospitalized with acute cardiovascular disease.

(2006) Bupropion: pharmacology and therapeutic applications.

(2006) Bupropion-SR, Sertraline, or Venlafaxine-XR after Failure of SSRIs for Depression

(2006) Use of bupropion in combination with serotonin reuptake inhibitors.

(2005) How does bupropion work as a smoking cessation aid?

(2005) Inhibition of CYP2D6 activity by bupropion.

(2005) Acute psychosis following sustained release bupropion overdose.

(2004) Intentional bupropion overdoses.

(2004) Bupropion insufflation in a teenager.

(2003) Bupropion poisoning: a case series.

(2002) Acute Psychosis after Administration of Bupropion Hydrochloride (Zyban™)

(2002) Bupropion exposures: clinical manifestations and medical outcome.

(2002) Seizure Induced by Insufflation of Bupropion

(2002) Bupropion treatment for cocaine abuse and adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

(2002) Recreational bupropion abuse in a teenager

(2001) Bupropion overdose in an adolescent.

(2001) A controlled clinical trial of bupropion for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in adults.

(2000) Bupropion is a nicotinic antagonist.

(2000) Cardiotoxicity associated with bupropion overdose.

(1999) A Controlled Trial of Sustained-Release Bupropion, a Nicotine Patch, or Both for Smoking Cessation

(1998) ECG conduction delays associated with massive bupropion overdose.

(1997) Fatal bupropion overdose.

(1993) Three fatal drug overdoses involving bupropion.

(1985) Bupropion–an antidepressant without sexual pathophysiological action.